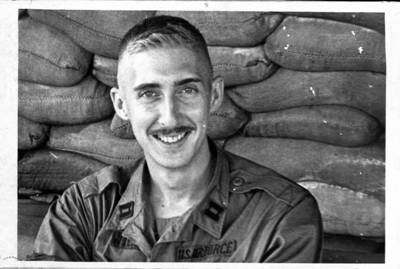

Dave Wiest

An HH-43F Story of Survival and Loss

In 1967, I was an HH-43F Rescue Crew Commander flying out of Bien Hoa. On the last day of March, we got alerted about 2:00 AM that an F-100 was inbound with zero hydraulic pressure. As we were scrambling with the fire suppression kit, we heard the radio traffic from his wing man saying Emergency, F-100 on fire, and calling for the pilot to punch out. We reconfigured for an off-base pickup and left for the coordinates given by the wing man. The site was about 10 miles northwest of the base. We flew there at 1500 ft, and there were solid clouds below us. An AC-47 Dragon-ship was orbiting, and we had two Huey gunships giving us immediate cover. We had communication with the pilot on the emergency frequency. He said he was okay and in a rubber tree plantation. From the topo map I knew the tree tops were at about 300 ft, and I decided to make an instrument letdown. The Huey pilots were not IFR rated (Thank you, AF); so, we would have to go down alone. I had my CP lean out his side of the Huskie and watch for tree tops while I started a circular orbit at a very slow rate of descent.

In 1967, I was an HH-43F Rescue Crew Commander flying out of Bien Hoa. On the last day of March, we got alerted about 2:00 AM that an F-100 was inbound with zero hydraulic pressure. As we were scrambling with the fire suppression kit, we heard the radio traffic from his wing man saying Emergency, F-100 on fire, and calling for the pilot to punch out. We reconfigured for an off-base pickup and left for the coordinates given by the wing man. The site was about 10 miles northwest of the base. We flew there at 1500 ft, and there were solid clouds below us. An AC-47 Dragon-ship was orbiting, and we had two Huey gunships giving us immediate cover. We had communication with the pilot on the emergency frequency. He said he was okay and in a rubber tree plantation. From the topo map I knew the tree tops were at about 300 ft, and I decided to make an instrument letdown. The Huey pilots were not IFR rated (Thank you, AF); so, we would have to go down alone. I had my CP lean out his side of the Huskie and watch for tree tops while I started a circular orbit at a very slow rate of descent.

The Dragon-ship sought to be helpful and started dropping parachute flares. The trouble was that the flares were swinging back and forth under the parachutes, and this caused an apparent horizon created by the flare light on the clouds, one that tilted up and down. This made it very difficult to concentrate on the instruments while trying to ignore what my peripheral vision was picking up--all very confusing. I called the Dragon-ship and had the flares stopped. Meanwhile we had gotten low enough that my CP could see leaves, and we leveled off just under the clouds. We were greeted by ground-fire tracers. Our pickup could hear us, but neither nor I was sure just where the other was. I told him I would flash my landing lights. (We were flying blacked out, no beacon or running lights) I flashed the lights very briefly, and the sky lit up with more tracers. Some were aimed at us, and some were between the VC and our forces. The pickup saw our light flash and gave us a relative bearing to him, and, as we moved towards him, we saw his flashlight signal. I had the crew chief payout about 100' of hoist cable and coil it in the cabin door way. I didn't want to take the time to run the hoist cable down. I told him to drop it out with the forest penetrator as soon as we came to a hover over the target. The pickup got clear of where the cable would drop; we hovered and dropped the cable, and the crew chief ran it down to ground level. The F-100 pilot got on the forest penetrator, and as soon as he was in the clear of the trees, I climbed up and out of there. More ground fire. We reeled him in on the fly. We were lucky and took no hits. The pilot, Capt. David Lindberg, was okay, and we climbed up through the clouds to 1500 ft and back to Bien Hoa. The irony was that some months later I would again find myself trying to rescue him at a crash site.

If it hadn't been for boot leg weapons, I would not be able to tell this story. While at Bien Hoa, I tried to get Rescue to issue us 45s instead of the aircrew-issue S&W 38s, but they wouldn't hear of it. The S&W was a fine gun, but in those days we didn't have speed loaders. Can you imagine trying to reload a revolver while running through the jungle? Then there was our boss, who was afraid of having a live round under the hammer, even though I showed him how the firing pin was blocked when the hammer was down. And then, they said we couldn't have the gun loaded until we were flying across the field boundary on an off-base mission. That was from headquarters in Saigon.

On the 21st of May, as usual, at 6 pm the alert crew brought the M-16s in from the alert bird and put them on a rifle rack in the alert shack. Unfortunately, the alert shack was air conditioned, and the rifle rack was open to the room. Anyway, about an hour later we got a scramble for an F-100 that went in about ten miles west of the base. We were later to learn that the pilot was our friend, Capt. David Lindberg. We found the spot of the crash; it was in a clump of 50 or so acres of woods. I had four Huey gunships (Heavy fire team) for cover, and thought to myself that this was going to be one of the safest runs yet. The Huey Fire Team told me the area was secure. The F-100 went down in one leg of an L-shaped clearing, and as I made a pass at 1000 ft over the site, I picked the other leg as an emergency autorotation site. On my third pass at 1000 ft, we could see the pilot's chute on the ground near the crash with the pilot's dingy. Another pass at 500 ft, and we failed to locate the ejection seat or pick up a beeper. I went to a hover, at about 100 ft, and the PJ was getting ready to go down on the hoist to check out the chute to see if the pilot was under it. Suddenly, an observer in another Army helicopter saw some VC step out of the woods and start firing at us from our rear. They were unable to communicate with us, because they had different radios. We couldn't hear the warning, because our frequencies didn't match.

On the 21st of May, as usual, at 6 pm the alert crew brought the M-16s in from the alert bird and put them on a rifle rack in the alert shack. Unfortunately, the alert shack was air conditioned, and the rifle rack was open to the room. Anyway, about an hour later we got a scramble for an F-100 that went in about ten miles west of the base. We were later to learn that the pilot was our friend, Capt. David Lindberg. We found the spot of the crash; it was in a clump of 50 or so acres of woods. I had four Huey gunships (Heavy fire team) for cover, and thought to myself that this was going to be one of the safest runs yet. The Huey Fire Team told me the area was secure. The F-100 went down in one leg of an L-shaped clearing, and as I made a pass at 1000 ft over the site, I picked the other leg as an emergency autorotation site. On my third pass at 1000 ft, we could see the pilot's chute on the ground near the crash with the pilot's dingy. Another pass at 500 ft, and we failed to locate the ejection seat or pick up a beeper. I went to a hover, at about 100 ft, and the PJ was getting ready to go down on the hoist to check out the chute to see if the pilot was under it. Suddenly, an observer in another Army helicopter saw some VC step out of the woods and start firing at us from our rear. They were unable to communicate with us, because they had different radios. We couldn't hear the warning, because our frequencies didn't match.

We took a number of small arms rounds, AK-47 probably, and I noticed that my needles were separating. There is a gauge with a rotor rpm and engine rpm needle. My rotor rpm needle was falling even though the engine rpm was fine. I turned 120 deg to my right and autorotated into the other leg of the clearing. While this was going on, I felt a slap on my neck which I though was the mechanic in the back of the aircraft hitting me to tell me to get out of there. (It turned out to be a bullet fragment that hit me).

Once on the ground, I shut her down and told the crew to run for a ditch a few yard in front of us. We all made the ditch and came under fire. We started shooting back, and all our M-16s jammed after a few rounds. So out came our other guns. The crew chief had a 45 Grease Gun he got from an Army buddy, the PJ had a 45, I had a Browning 9mm, and my co-pilot used his issue 38. With the gunships blazing away--and all the ground fire--you could hardly hear yourself think. I had had the radio shop rig my emergency radio to plug into my flight helmet; so, at least I could hear the radio. A Huey (Tomahawk 18) got into the clearing behind us, and we made it out of there. We took a lot a fire and just made it over the trees. When the Army pilot dropped us at Bien Hoa he was some pissed as it was a brand new bird, and now it had a bunch of holes in it. It took two cases of scotch to sooth him.

My helicopter was fine, just needed a new engine. Some rounds had got in over the armor plating and wiped out my turbine buckets, so the engine ran fine but didn't produce any power. By now it was late in the afternoon, and the light was going fast. They couldn't secure the area and get a lift copter in to get it out; so, they called in an air strike to destroy it. They shot the hell out of it, but because of self sealing fuel tanks it wouldn't explode. So they called in artillery and blew it up so that Charlie wouldn't get any use of it.

Meanwhile, we were sent to the Flight Surgeon for an after-action physical, required after being shot down. We were told to pile our clothes in the corner. I was concerned because of all the non-issued weapons, handguns, grenades, and stuff; so, I asked the doc not to look too closely at the pile. He laughed and told me he wasn't looking at that, but at us. The PJ had taken a round in his thumb, and I had a piece in my neck, but other than that we were fine and patted on the back and sent back to duty.

I was awarded the silver star for the rescue of Capt. Lindberg and the DFC for the second attempt.