Lew Price

A Taste of Life

in

Military Air Transport Service 1961-1965

(a five-year autobiography).

Copyright (C) 2003 by Lew Paxton Price.

[Webmaster note: This is a long and detailed account of Lew's experiences while on active duty. It is interesting reading, but it is not likely that you will read it in its entirety at one sitting. Lew has thoughtfully provided the links below to facilitate your resuming where you left off when you return--Thanks, Lew]

Prelude

In primary pilot training, I lost three days due to the flu and never caught up. Just before everyone else went to the next base for pilots, I washed out. This bothered me a lot at the time.

A colonel had a little talk with me. He had gone to great lengths to get me a plush assignment as a navigator in Military Air Transport Service (MATS). He explained that it was a great place to go as a navigator, and he asked if that made me feel any better. I did not look any better than I felt, but it turns out he was right, and I should have been more grateful. In school I had taken geography and history--and learned very little of value. In MATS I really learned a lot of geography and history--as well as a lot of other things.

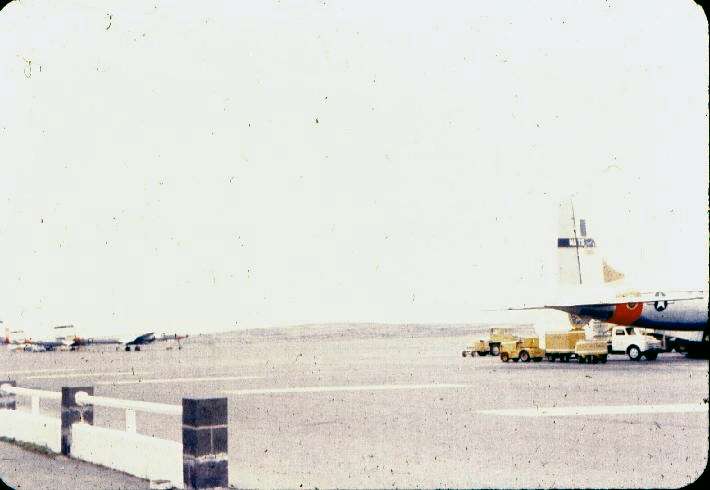

My due date to report to my new assignment was 15 Dec 1961. I reported early to the headquarters of the 30th Air Transport Squadron (ATS) McGuire AFB in New Jersey. McGuire was named after Tommy McGuire who was a P-38 ace in the Pacific in WWII. The 30th ATS was flying C-118s, and they needed more navigators.

The C-118 was a four-engine transport that was considered "medium" at the time. Douglas made it to improve upon the C-54 of WWII fame. It had the power on two of its four engines to do what the C-54 did with all four of its engines. It cruised at 240 knots which it made it easy for a navigator, because its airspeed was almost precisely four nautical miles per minute. It also had a roll that was two minutes in duration. Most airplanes have a natural roll as they move along, but a two-minute roll was special, because that was the precise time it took the averager on a periscopic bubble sextant to complete its work during a shot. This feature allowed a navigator to have pinpoint celestial fixes when the sextant error was known.

The C-118 came in two basic forms. There was the 1951 model and the 1953 model. In most ways the '53 was better, but the '51 had a drift meter (a hole in the floor that allowed one to discover the ground speed and course if there were stationary objects below). The drift meter was needed for flights across places like the Sahara Desert. The floors on both models had been beefed up for carrying cargo, and sometimes this was extremely useful.

The crew compartment consisted of a bulkhead behind the two pilots, a place behind on the left for luggage and crew bunks, and the navigator's station behind on the right with four seats behind that. This was the layout of the '53 model. The '51 was different, and included a latrine behind the navigator's station.

The engine analyzer for use by the flight engineer was located on the right of the door frame to the cockpit. The engineer's seat was removable and was located in the doorway when in use.

The hole for the periscopic sextant was in the center behind the navigator. One needed to climb on a stool to put his eye to the eye-piece. Once in flight, the sextant was mounted and left there until it was no longer needed. It was packed away before landing.

The RADAR set was an APS-42 with the screen to the left of the navigator and was controlled by the navigator. It had a pencil beam and a mapping beam, could be held to sweep back and forth through a sector or sweep 360 degrees around continuously, and could be adjusted up and down--but that was only when it was working. It was a tube machine that often quit when it was needed. The APS couldn't take power surges well; so, it had to be shut off right after landing before the props were put in reverse to stop the aircraft.

The LORAN set was to the right of the navigator. It was also subject to tube failure. Tubes for the LORAN and the RADAR were available, and in-flight repairs sometimes worked.

The Identification Friend or Foe (IFF) controls were in front of the LORAN set, and the navigator would set the proper squawk on it when the controller on the ground requested it.

There was another door to the outside where the navigator's table was located. One of the things the navigator always checked was the door-holding mechanism and its safety strap to make sure the door was properly secured. The table was put in place after takeoff and removed before landing.

Most of the time, the C-118s carried people--usually 68 of them plus the crew. Sometimes there were those who were more than people (called generals). The 30th was considered one of the VIP carriers who landed at Andrews from time to time to pick up such people. Sometimes the C-118 performed air evac missions. When people were carried, there were flight attendants on board, usually female, who served the passengers from big ovens in the left rear of the fuselage. The ovens could be removed for cargo flights. They could sometimes be a problem: like the time a C-118 took off into a tornado and was forced down into a forest at the end of the runway. All the passengers on the left side were crushed by the ovens as the plane abruptly stopped.

The people varied, but when the Army had their boys in the airplane, the Air Force enlisted men who serviced the airplane had nothing but comic books to choose from after the Army left. If it was the Navy in the airplane, there were a lot of pornographic magazines and sometimes even one as "uplifting" as Playboy could be found. If there were Air Force people (which was most of the time), there were magazines left like Field and Stream and True.

Most of the flying was through weather--or so it seemed. The 118 had de-icer boots on the wings that helped when icing was occurring. However, the best solution for icing was an altitude change. Ice formed when the outside air temperature was about 34 degrees Fahrenheit. Freezing for water occurs at 32 degrees, but the air over the wing or into the engine carburetors was more rarified and caused the temperature to drop from 34 to 32 degrees. When icing occurred the plane could go up to an altitude where it was too cold for icing to happen--or go down to an altitude where the air was too warm for icing to happen.

The LORAN antennae was a long wire on top of the fuselage and would often take on ice. This was not usually considered a reason to change altitude; so, the navigator would be without this nav aid when icing occurred there. This type of icing did not seem to affect the wings or carburetors.

Of all the electronic nav aids, the RADAR altimeter was the most reliable. I never had one fail; so, pressure pattern was always available to use over water as a measure between the heading and the actual course.

In MATS, all aids that could be useful to the navigator were to be used. LORAN was one that could be accurate to within 50 feet when close enough to its broadcasting stations. It was better than nothing when farther from those stations. Celestial was good when there were no clouds above and partly useful when there were spaces between clouds. However, it was critical to take a good three-star fix when possible so that the sextant error could be discovered for that particular instrument--otherwise celestial single lines of position would be in error. Pressure pattern was extremely accurate as long as the RADAR altimeter and the pressure altimeter readings were begun right away--this always gave a perfect course line when computed and plotted. When nothing else was possible, the waves on the ocean could give an idea of wind direction and velocity. Clouds could provide the shear levels and wind directions. Radio was good when close enough to the radio transmitter. Of course, there was map reading and RADAR fixing when the RADAR was working.

During WWII, the Germans developed a type of navigation, used to vector bombers to London, called CONSOL. There was at least one occasion when knowing how to use this nav aid saved us. It was primitive, but would get through to a plane when nothing else would, consisting of a system of dots and dashes over a particular radio frequency. It had a range of 800 miles over land and 1,000 miles over water.

The most critical aids for navigation were the weather progs. These were forecast maps of wind velocity and direction along with the highs and lows for two altitudes and for certain time periods. Using them was like using dead reckoning except it was more like "live" reckoning. One could plot the plane's course on the prog and interpolate for altitude and time. Then the navigator could compare this to the wind that was encountered previously to determine the likely drift and ground speed for the near future.

In MATS, there was the basic crew of two pilots, one navigator, one flight engineer, and one loadmaster or flight attendant. Such a crew must rest after 16 hours of crew-duty time. Crew-duty time is defined as time on the ground or in the air while working. There is an augmented crew in which one each or more of the crew types are added to the list of crew members with the exception of the flight engineer which can remain one only. This type of crew can have a much longer crew-duty time. This is because the crew bunks are available, of course, with people to use them.

On airways, the radios are used by the pilots to navigate, and the navigator need not work. Once off airways such as over an ocean, at or near the poles, or over the Sahara, the navigator is working while the rest of the crew can rest with exception of one pilot who often seems to go to sleep in the cockpit. The navigator can be very busy when part of a basic crew.

Upon reporting to the Squadron Commander, I was provided with plenty to do: like being vaccinated for everything in the world, getting a passport, taking classes in various kinds of survival, etc. Flights from McGuire were of two basic varieties. One was the more usual type that happened (these always had a backlog). The other were flights that came up due to the changing conditions in the world. We flew everywhere except into communist nations--and that could change.

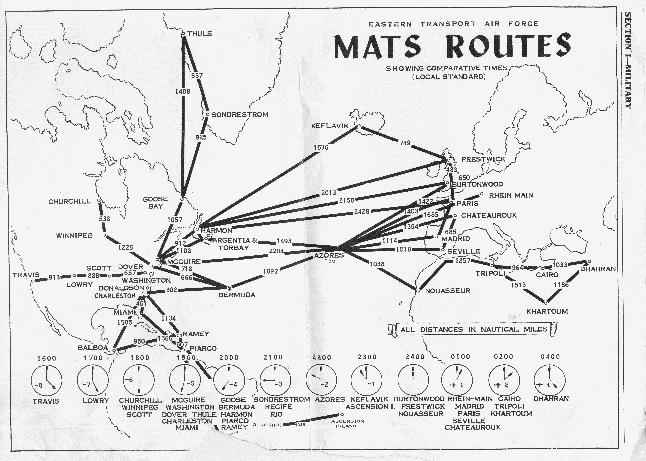

Scheduling set me up with an orientation flight to Europe so that I could see a real MATS crew in action. The crew wore class A uniforms on these passenger flights just like airline captains wore. The route was McGuire; Harmon, Newfoundland; Prestwick, Scotland; Rhein-Main, Germany. This was the most common route taken by the 30th. Others went to other points in Europe like Paris, Madrid, and Mildenhall in England. There was a common run to Ascension Island which meant a couple of stops in Recife, Brazil, where the bulk of the squadron's coffee was picked up. (The only way we could afford all the coffee we drank was to use Brazilian coffee mixed with Maxwell House. The Maxwell House was much better but more expensive.) There was a run to Thule, Greenland; another to Churchill, Canada; and a Bermuda turnaround. When we went west, we went through Hawaii to Guam, Wake, or Midway--and from these to the Phillipines, Taiwan, Okinawa, or Tokyo.

One of the things I realized right away was the complete and total difference between navigating as taught by the Air Training Command (and the Academy) and that which must be learned in actual line navigation. Both ATS and the Academy were way behind.

After we arrived at Rhein-Main, we were able to rest and have some bratwurst, sauer kraut, and mashed potatoes in Frankfurt. The flight back to Prestwick was fine, but when running up the engines prior to take-off at Prestwick the flight engineer noticed a problem with the number two engine (using the engine analyzer), and we wound up staying at Prestwick at an "after new year" new year's party. The host's daughter was mixing drinks and giving them to us, and she got carried away with the proportions of gin and orange juice. I came down with a terrible cold, and it was fortunate that we did not get the airplane fixed for a few days. I have had an aversion to gin ever since.

On the way back I found out that the navigator is also responsible for filling out the per-diem forms. The flight calculations were based upon Greenwich mean time (GMT--sometimes called "Z" time), but the per diem is based upon local times. Per diem means essentially "living cost per day". There were bureaucratic rules on how much for each location would be required for average quality meals and lodging. If one were frugal, the allowance could supplement one's income slightly. Per-diem computation is complicated. As if this were not bad enough, when flying in the Pacific the international date line is crossed; so, sometimes we seemed to have arrived before we left, or to have required two days to fly only a few miles.

Return to MenuTraining Period

Squadron duties included flying, taking turns at being the duty officer, an additional duty (such as personnel officer, administrative officer, flight commander, custodian, intelligence officer, pay agent, administrative assistant to the commander, etc.), and odd jobs such a leading the Air Force contingent in a ticker tape parade in New York.

There was alert duty for emergencies. The quick response type kept the crews in the visiting officers quarters (VOQ) on base. Home alert meant staying at home with your bags packed. When at the VOQ, there was a lot card playing. I read a book on poker just so I could 'stay even' even though they were not high-stakes games.

There was local flying which meant testing airplanes coming from the consolidated maintenance squadron that were supposedly repaired, practicing in-flight emergencies, and checking sextants (for the navigator). At the end of each year there were a lot of locals to burn off the gas that had been carefully rationed during the year. If the expenses were not up to the budget we were allocated, Congress would cut the funds for the coming year (a stupid system).

After returning from Europe on my orientation flight, I found I had been scheduled for a number of courses prerequisite to becoming a qualified MATS navigator. I had already taken the course on ditching which involved using a warm swimming pool and was nothing like a real ditching in the North Atlantic. Ditching for real usually meant going down at night in a storm using the light from parachute flares shot out through a hole in the crew compartment for that purpose. The pilot was supposed to land in a trough between waves and land parallel to the waves. Otherwise, the plane would break in half. This sounds easy except for the fact that there were always secondary swells which meant at least two other systems of waves besides the primary; so, the pilot had to see all this and make sure to land so that all the swells were allowing the necessary trough to exist.

The North Atlantic is cold. When one is in the water, he or she has about 20 minutes to get in a life raft before turning blue and drowning. The life rafts are stored above the passengers. They must be pulled back to the door, taken out, and inflated before the plane sinks. This must be done in an orderly fashion with no light except that coming from flashlights. The passenger seats in the 118 face to the rear, and they have tall headrests; so, chances are, the passengers would survive the impact. But getting the twenty-man life rafts out of the door by moving them over the passengers could be a problem unless the passengers were able to help sufficiently. To top it all off, the survival equipment, including the rafts, had only a 50 percent rate of reliability. Half of them would fail. The budget did not allow for more reliable equipment, and what we had was old. So we were very much against ditching.

In the ensuing days, I was given basic and combat survival, and RADAR and LORAN familiarization so that I could make in-flight repairs. I met my navigation instructor and was scheduled for my first flight instruction (26 Jan 1961).

Before each mission, the navigator would find the correct time. I am not sure what the navigators did, but I had a shortwave radio that could be tuned to WWV in Greenwich, two watches that were both good ones, and were with me so I could be sure of the time. There was a briefing at the squadron headquarters prior to going to the airplane, and the navigator provided the time hack for the crew at the initial briefing. The aircraft had several clocks that had to be set during the preflight check. Having the correct time was critical for celestial navigation, and correct navigation was critical in case we had to be found in the water after ditching (God forbid).

Navigators carried large briefcases with lots of charts in them, because we might not be able to obtain the correct ones in foreign lands if we were needed elsewhere suddenly. The charts we normally used covered large areas and were usually sufficient to take in the entire route of flight for one complete mission direction. Aircraft Position Charts were used by commercial airlines. They were a lot smaller than our Global Loran Navigation Charts (GLCs) or our Global Navigation and Planning Charts (GNCs), with a ratio of one mile to 6,250,000 miles. We had the airline type of charts in our briefcases, but we seldom used them except for references. Our GLCs had LORAN lines on them; so, we used them most of the time. Both they and the GNCs had a ratio of one mile to 5,000,000 miles--meaning that a pencil line was about a mile wide on the chart. There were also route charts (1:2,000,000) which were laid out in strips for airline route use. They lacked the luxury of seeing what was outside of those strips. And there were Operational Navigation Charts (ONCs 1:1,000,000), World Aeronautical Charts (WACs--1:1,000,000) and Sectional Aeronautical Charts (Sectionals--1:500,000). We used the ONCs for greater detail of island chains in the Mediterranean and Caribbean. The WAC charts were best for RADAR navigation. The sectionals were used for approaching and leaving hotspots or trouble spots where we wanted a lot of detail. Lastly, we had Local Aeronautical Charts (Locals--1:250,000) which were used when we wanted even more detail on trouble areas.

The MATS navigator's log was much more abbreviated and efficient than the ATC version, with more information in it. The log was very important, because it carried the same weight as a ship's log and could be used in court or for purposes of investigation when such things were necessary. In addition to the log, the navigator made out a Range Control Chart which showed the estimated and actual fuel used for the time flown. Readings for this chart were given to the navigator by the flight engineer who used the fuel flow meters rather than the fuel gauges to come up with the correct answers. The fuel gauges were always incorrect. They were checked periodically, and little red marks were put on them to show how far off they were.

I was also given a course in Electronic Countermeasures (ECM) which I later found useful when we were attacked electronically. The navigator was the designated ECM officer on board. It was supposed to be a cold war, but being killed by electronic means makes one just as dead as being killed by a missile or gun.

There are numerous squall lines in the North Atlantic that must be penetrated by any airplane that normally cruises at altitudes lower than 20,000 feet. Hopefully, the RADAR will hold so that the navigator can tell the pilot how to avoid the cumulonimbus formations. With the RADAR on pencil beam, forward sweep, aimed at the same altitude, and with the correct gain, the hearts of the giants can he seen and can be avoided (usually). Entering one can cause severe damage to the aircraft.

During my first training mission, I failed to meet the speed requirements that Neal, my instructor, set for me. When I attempted to do something right, he would complain that I was too slow and needed to get more done. His technique was to have at least six lines of position (LOPs), and preferably ten or more of them. He would have them crossing at odd angles, never a pinpoint, and would then choose the center of the mess and say we were there. Of course, most of the LOPs had to be adjusted to actual time for the fix, because they were taken at other times. I realized later that Neal never knew where we actually had been at the time of the fix. I eventually referred to this style of navigation as "the shotgun approach."

At the time, I did not know any better and tried to do what Neal told me to do. Needless to say, I was not recommended for a check ride after this training mission. The Chief Navigator for the squadron was not happy. Brad Hosmer had been there the year before and had checked out in one ride. Therefore, all Academy grads should do the same. The average number of training missions for navigators was four. It took me six with Neal bothering me about speed before the Chief decided to give me a new instructor. During the ride I took with the new one, I was still trying to do what Neal had told me to do. However, I was given an OK for a check ride from a flight examiner. By this time, I was nervous and frustrated.

Something of interest occurred on one of the training flights on which there was another navigator on board. I will call him "Mark" which is not his real name. We arrived at Rhein-Main in the wee hours of the morning locally, and I overheard Mark and Neal conversing. They proceeded to fill me in on the conversation.

Mark lived in base housing where the walls between "apartments" are rather thin, and one gets to know his next door neighbor well. The night before going on this flight, Mark's neighbor was obviously very angry, and Mark asked him why. There was a contingent of F-106s at McGuire. The neighbor was an F-106 pilot. He and his wingmen had been scrambled to intercept an object that had been discovered by two ocean-station vessels (our east coast RADAR picket line) hovering at a high altitude off the coast.

The 106s climbed to altitude and converged on the object. It looked like a green ball, and the 106 RADAR sets picked it up, reinforcing the visual sighting. As the interceptors approached it, the object began to climb straight up. The 106s went up after it, and it left them far behind, disappearing in the distance.

When the pilots came back for their intelligence briefing, the intelligence officer attempted to make them sign a report indicating that the first pilot was seeing a reflection in this windscreen and the second was seeing the jet exhaust of the first one. The pilots refused, and there were veiled threats. Consequently, they were angry when they arrived home.

My flight examiner was Pappy Grant. He was in the Air Force as a hobby. His full-time job was blueberry farming, and he was studying bionics now, having a degree in marine biology already. He was never sloppy, but he always looked like a blueberry farmer. He was also something of a philosopher and taught me a lot as time went by--like not picking up anything while skin diving because it might be poisonous.

Pappy got to know me on the way to Newfoundland when we were still on airways. When we left Newfoundland he looked at what I was doing as I started to navigate.

"What are you doing?" he asked. I told him what I thought I was doing.

"You are doing it all wrong," he said, "Slow down. Accuracy comes first, and speed will come with time and repetition. Let me teach you a few things on the way over, and you can show me what you can do on the way back."

He then showed me how to investigate the waves on the LORAN set to see which stations were reading accurately and which ones were not. He showed me how to make a transition when good ones began to fade and others would become prominent. He told me that two or three good LOPs meeting at a pinpoint were superior to ten that were widely spread out. He showed me how to use the progs and our instruments to tell how the wind was shifting. By plotting our course and the prior-known winds on the progs themselves one could see how the highs and lows were shifting. He made sure that I used the first opportunity to use a classic three-LOP celestial fix to check the sextant error. Most of all he showed me how to take my time and get the correct results--just like I had always wanted to do. When we arrived at Madrid he showed me how to down a delicious mixed grill at one of the best restaurants.

Pappy told me to forget what I had learned from Neal so that I could start with a fresh slate and have room in my head for what Pappy could teach me. On the way back I found that it was easy to navigate the 118. Pappy gave me a thumbs up, and in his report he said "Lt. Price's chief difficulties encountered on this trip stemmed primarily from attempting to work too rapidly. This tendency was (unintelligible) created by 'checkitis'. He will undoubtedly develop into one of our better navigators with further seasoning. He is qualified to perform the duties of a MATS transport navigator." I was expected to initial this, and although I did not for one moment believe that checkitis had anything to do with my working too rapidly, I realized that Pappy was giving Neal a break, and I initialed the report.

The next time I saw Neal was on a Churchill, Canada, flight; he was a staff officer who no longer flew except to get in his flight time to get his pay. There was no mention on the flight orders of his being an instructor, but this could have been a simple omission. By that time, I was seasoned and not willing to conform to anything that did not make sense to me. I did not believe that he had deliberately meant to teach me the wrong things; so, I had no grudge against him. We got along well enough by staying out of each other's way.

Return to MenuSurvivor

On 5 June 1961, I attended a course called "Nuclear Weapons Training" while simultaneously doing duty on home standby. We were allowed to do other things while on home standby as long as we told the squadron duty officer where we were and carried our packed bags with us.

We were being pushed hard most of the time. The average flight time per month was supposed to be 110 hours. The max was supposed to be 125 hours. Exceeding this was not good for us; so, we usually were not overloaded. There was a time later when I began to develop mild symptoms of combat fatigue, but I got over it. I noticed later that my number of recorded flying hours was incorrect. I actually had about 200 hours more in MATS than the 4,600 plus hours that was listed. Once I figured out our average work hours per month including training, duties, and flying. It came to an average of about 360 hours per month as compared the average civilian load of a little over 160 hours of work per month. There are only 720 hours in month on average, and 240 should be used for sleeping. So the number of waking hours, including time to eat, comes to 480, making the free time including eating 120 hours--which is 4 hours per day, and that is usually taken by other necessary tasks like paying bills, etc.

Most of us began to hate telephones, because they meant leaving home again on short notice--sometimes before the wife could even wash the dirty laundry from the last trip. Some managed to either ignore the phone or leave home between scheduled flights. We were never able to enjoy ticketed events like Broadway plays, concerts, opera, etc. But the seafood restaurants were available at a moment's notice, and sometimes when going through Harmon, Newfoundland, we could take a half-dozen lobsters home in the unheated baggage compartment below the passenger deck.

On 19 June I was the navigator on another trip to Rhein-Main and back. On the leg from Rhein-Main to Lajes (Terceira in the Azores) the LORAN antenna iced up badly, no celestial was possible, there were no radio stations available for our use, and we still had to find a way to arrive at a little island after 600 miles with no fixes. All I had was the weather progs, pressure pattern, and my best guess on how the winds were shifting. After 2 hours and 45 minutes in the weather we came abeam Lajes and only missed it by 12 miles. This was some of the best educated guessing I have ever done.

In the summer of 1961, I met a navigator who survived a crash into the forest after taking off from McGuire into a tornado. His broken neck had healed, and he was still flying.

Before the crash, the plane had been cleared for take-off--right into blackness even though it was daylight. There had been pressure from higher up to keep the schedule; so, no one in the crew attempted to stop the take-off.

The plane attempted to climb, and encountered a downdraft. All possible power was added, but the plane still came down and hit some trees so that the wings swiveled forward and the inboard engines went into the crew compartment. The surviving navigator was in the passenger compartment on the right side. His seat belt was not tight enough, and the downdraft caused his head come above the headrest in the rear facing seat. As the plane ground to a very sudden halt, his neck was broken.

The ovens on the left-forward part of the passenger compartment came forward and killed those on that side. One survivor managed to get out and bring help. When he succeeded in finding a road, some MPs from Fort Dix picked him up and threw him in the drunk tank, disregarding his story completely. Half a day later, someone noticed that an airplane was missing, and the wreck was eventually found--after almost all of the injured had died.

The circumstances of this crash became legend, and, for a time, the policies at McGuire changed to prevent such a thing. Also for a time, the idiots comprising the military police at Fort Dix were a little more careful who they threw in the drunk tank. From that time on, anyone on the flight deck at the time of take-off could call an abort. This rule was kept with flight crews since--regardless of any pressure from above.

It was about this time that another navigator told me his secret for not being bothered when he arrived home after a trip. First he took the phone off the hook. Second he took a shower. Third he took two rolls of 50 pennies each that he always had ready for this purpose, removed two pennies from each roll, scattered the rest in the yard, and told his kids to find the 100 pennies. Fourth, (you can guess what). After that he gave his wife the dirty laundry from his B4 bag.

Return to MenuGrid Navigation

On 7 July 1961, Lt. Larry Arnold gave me flight instruction on grid navigation. In most latitudes we relied heavily on magnetic compasses. The magnetic north pole is not the same as the geographic north pole, and the longitude lines coverge at the geographic pole. The confusion from these facts and their consequences caused polar navigation to become grid navigation in which a gyrocompass takes the place of the magnetic compass, and a grid is superimposed upon the map. Gyros precess for three reasons: (1) earth rotation, (2) earth revolution, and (3) mechanical friction. So it is necessary to check the amount of precession with time in addition to taking fixes. The airplane's autopilot follows the gyro that is precessing, and as it precesses, the airplane actually flies a series of curved courses between corrected compass headings.

At night, one can use Polaris to check the heading to see what precession is being experienced..During the day, one uses the sun, which involves a lot of celestial shots. One must also keep log or graph for precession. Coriolis force is very strong near the poles; so, this means winds can change direction and velocity very abruptly and very often. In short, there is a lot more for the navigator to do. If the RADAR works, the navigator can usually use its mapping mode to take fixes. Otherwise, more work is needed. Overall, grid navigation is a much more difficult proposition that normal navigation.

To add to this, the crew must essentially memorize a large manual on arctic problems and how to deal with them. It is much easier to die from not being on course if the plane goes down, because it will be more difficult to find for rescuers with dog sleds.

On this flight we only flew as far as Sondrestrom, Greenland, via Goose Bay, Labrador. We had an augmented crew; so, we were able to arrive back at McGuire after 27 hours of flight time without crew-resting. Larry Arnold reported that I was ready for a flight exam on grid navigation.

Goose Bay, Labrador

On 11 July I had another trip to Mildenhall, England, via Harmon and Prestwick. Then on 24 July I was on crew going to Thule, Greenland, for my flight examination on grid navigation. We crew-rested at Thule for a day.

In the summer at Thule, the sun is up all day long, and leaving the officer's club at 11:00 PM with the sun staring you in the face in unnerving. The base is close enough to the glacier that guys can hike there and chip off blue ice that has been under extreme pressure for millions of years. Then they can go home to New Jersey and use the ice at a cocktail party during which the ice keeps making cracking noises as it decompresses.

The base has central heating that is moved over the ground (one does not dig easily in perma-frost) in cylindrical insulated ducts which form an inverted "U" over the roads (for an expansion joint and to allow traffic to run under the duct. There are small, double-paned windows that cannot be opened in the greatly-insulated buildings. Instead, there are holes in the walls a little over an inch in diameter with discs of metal that can be rotated over them when ventilation is not wanted. The exterior doors have shelves at their bottoms which overlap the door frames so snow cannot come between the frames and the doors. There is survival gear in every building in case of a phase, which is when the exterior temperature, wind chill factor, and/or snow becomes so extreme that survival outside becomes nearly impossible. Runways are metal grating lying over the perma-frost.

When an aircraft lands in winter, it is placed in a large hangar where the oil is drained from the engines and kept warm until it is time for take-off. Then the warm oil is poured into the engines, the engines are started, and the plane is able to take off. On this flight, this wasn't necessary, because it was summer at Thule.

The aspect of the base is a grayish-brown with various shades of white when snow falls. There is said to be a woman behind every tree, but there are no trees or bushes at Thule. Many of our WAFs would arrive smiling and poor, and leave tired and wealthy, having sent as much as $500 back home to their bank accounts in a time when that was a lot of money. Although the guys usually disliked the flights to Thule, the gals loved them.

There was no fence around the base to keep the guys in. The harsh conditions do that very efficiently no matter how crazy they become from being confined for long periods without feminine companionship. One kid sought to stow away in the nose-wheel well of a C-118 one summer, but the jar of the landing caused him to fall out, and, in his frozen condition, he shattered all over the runway. Another time, two men decided to escape in the winter across Baffin Bay toward the base at Goose Bay. The water in the bay is frozen in winter; so, one can walk across it. Their exit was discovered when they failed to report to work, and their precise location was discovered by air as they made their way south. Nothing was done to apprehend them until they reached Goose Bay. Then they were brought back without having their records adversely affected--and kept at Thule for some time as arctic survival instructors.

Another time, an aircraft was unable to land due to bad weather at both Thule and Sondrestrom. There was not enough fuel to continue; so, the crew prayed while the pilot began a very slow descent through the undercast. The plane dropped lower and lower, the altimeters unwinding very slowly. Then the altimeters seemed to be stuck. The engines were going strong, but there was no evidence of motion. Suddenly there was a man standing in front of the plane signaling to shut the engines down. The engineer had looked outside and then noticed some white ridges just below the fuselage. He had opened the door and dropped out the dipstick which remained upright stuck in some snow. So he decided to go out and tell the pilots that they had landed. The airplane is still there.

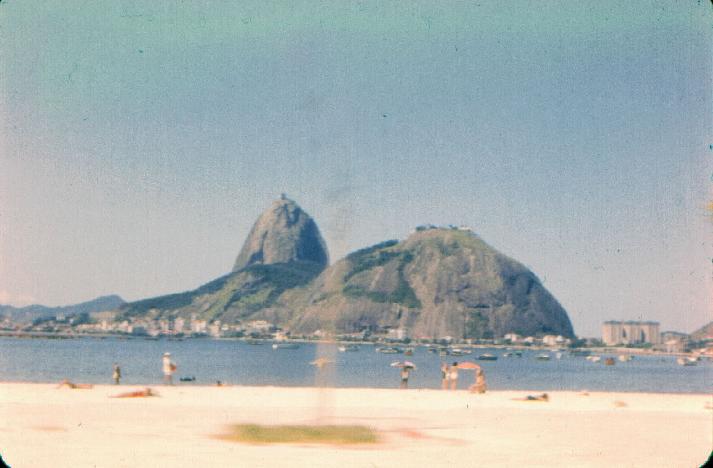

I was checked out as a polar-qualified navigator on this flight. Later, I was told that this was the first time anyone had been recommended for a polar check flight after only one polar flight or had become polar-qualified on the first polar check flight. I had lived for years in Michigan before going to the Academy, and cold weather survival seemed like normal living for me. As a result of this and the unprecedented first, I was scheduled for a series of flights to the north country--and this trend continued. To be fair, I should mention that scheduling later rewarded me with a flight to Rio de Janeiro, something that rarely ever happened.

Return to MenuCairo

Somewhere around the 10th of August, there was a locust plague in Egypt. I was one of the crew that was sent to Andrews AFB to pick up a cargo of bug dust in big drums. The seats had been taken out of the 118, and the drums tied to the rings on the floor.

Two pilots were doing silly things to one another (so-called practical jokes). Most of us would have probably put one in the hospital for some of those things, but they didn't bother anyone else. The worst thing was when one left the cockpit to go to the latrine (in the tail). The one still in the cockpit waited a few moments and then pushed the wheel forward followed by pulling it back abruptly. The guy came out of the latrine with a flying suit soaked from head to foot with what had been in the honey bucket. I doubt if he had another flying suit, and we had no showers on the airplane. I hope he somehow managed to beat the other pilot silly later on, but if he did, I never knew about it.

We had a chance to land at Cairo and see some aircraft from other nations. There was a Tupolev 104B painted white and light gray with red markings. The "A" model had set an altitude record for its type on 6 Sept 1957--12,000 meters (36,814 feet) while carrying 20,053 kilograms (44,209 pounds). On 11 Sept, it set a route speed record of 897.498 kilometers per hour (557.67 miles per hour). It was a picture of husky sleekness, its two large jet engines located against and as part of its fuselage were the approximate equivalent of four of our engines. There was a French Sud-Aviation SE.210 Caravelle III. This type came out in 1959 with two Rolls Royce engines developing 11,400 pounds of thrust each. Its cruising speed was 484 miles per hour and it carried 80 passengers.

The pyramids were in the distance and we could see them during landing and take-off, but from the sky even the great pyramid was very small.

There were no flies on board the plane on the way to Cairo, but there were some on the way back.

The wing later received a letter of commendation from the American Ambassador to the United Arab Republic (Egypt) for our prompt and much appreciated response to the locust plague. We worker bees received copies of it.

It was in August of 1961 that the Soviet Union erected a wall between East and West Berlin. This caused a bit of trepidation among us. We did not want to have another Berlin Airlift with MIGs making head-on passes to try to drive us off course. Fortunately, nothing more happened for awhile.

Return to MenuFuel Problem

There was a "pony express" mission to Wheelus in Libya, and we left on 18 Sept 1961 deadheading to Harmon where we crew-rested for a day before flying our own plane to Rhein-Main. There we crew-rested for two days and then flew another plane to Wheelus. At Wheelus we crew-rested for a day and then flew to Torrejon in Spain. There we crew-rested again briefly and then flew to Lajes in the Azores. There we crew-rested again before flying to McGuire via Kindley in Bermuda. I refer to this as a "pony express" mission, because the idea was to take an airplane straight from start to destination by simply changing crews (like the horses were changed for pony express riders).

On climb out from Wheelus late on the 23rd, flying in the dark, there was a loud explosion from our number two engine and a lot of abrupt flame, followed by silence and darkness as the pilot feathered the engine. We went back to base for another rest while the engine was changed. It had blown a jug (from too much manifold pressure for the RPM perhaps?). We landed and blocked in just one hour after take-off. The next day we took off with a different 118 and arrived at Torrejon without further difficulty. Nor was there any problem on the way to Lajes.

There is a little book that was given to all C-118 navigators that is called the MM 55-9 or FUEL PLANNING MANUAL. Under normal conditions, it is used to plan fuel for a flight. One enters the aircraft gross weight and expected altitude of the flight; the expected duration of the flight, should have been calculated from the expected winds aloft; the course; and the average true airspeed (TAS). The expected flight duration plus ten percent, plus holding time in case of a delay in landing, plus time to the alternate, plus time for approach and landing, provide other necessary figures. This gives one the ability to go into a graph and determine the expected fuel that will be required for the flight as well as the amount of fuel load that should go into the fuel tanks.

It is possible to do other things with the MM 55-9 when one spends a little time thinking about it, even if it was not really intended to be used in such a fashion. The slope of the fuel line varies with the power setting, and the fuel used per hour for various power settings can be determined by looking at the appropriate part of the fuel line. To maintain the correct airspeed, a higher power setting is required early in the flight, because the airplane weighs more. As the fuel is burned off, the gross weight decreases, and the airspeed increases; so, the power can be reduced. These reductions continue throughout the flight, and the airspeed curve is a stepped line that can be averaged if one wishes to do so. If someone wishes to increase the power setting, the fuel to be used can be calculated--not easily, but correctly. However, we were not taught how to do this.

As we took off from Lajes, the weather was becoming bad, with blowing rain and a low ceiling, but we were able to take off without difficulty. We turned toward Kindley immediately and climbed on course, and I began to take RADAR fixes off the islands. At 12,000 feet we leveled off, and I took a LORAN fix and then checked it with the ADF's (automatic direction finders--radio). We seemed to be moving very slowly. About half an hour later, about an hour into the flight, I took another fix, and the engineer passed me the fuel readings. When I plotted the fix and the fuel readings it became apparent that we were facing a very large and unpredicted headwind.

I examined the weather prog and realized that the headwind was likely to dog us most of the way to Kindley and that we were likely to run out of fuel before we ever arrived. I then advised the aircraft commander (AC) of the problem.

The copilot called Lajes back to tell them we would like to return. They advised us that the weather had closed in the field, and we could not land there. Our alternate for Lajes was Santa Maria, and it was also closed down due to weather. In fact, the entire group of islands that comprised the Azores was expecting to have low clouds and fog for many hours after we would have run out of fuel, and Europe was too far away for us to go there.

We dropped down to 8,000 feet in an attempt to find a flight level that would have less of a headwind, and I started doing some calculations on range control. After a few moments, I concluded that we might be able to reach Kindley in Bermuda by increasing power to the engines if we did so very quickly. According to the fuel planning manual, this was possible, but still risky if we should happen to find a stronger headwind later in the flight. I had been tracking our progress with good speed lines and realized that even at 8,000 feet the headwind was much too strong. So I plotted my solution on the range-control chart and stuck my head into the cockpit to talk to the AC.

At 8,000 feet, the wings were icing up, and the pilots were becoming concerned. Ice will not build upon a wing if the outside air temperature is high enough above freezing, and that is what we usually depended upon in a storm at our usual altitudes. Nor will ice build on a wing if the temperature is at freezing, because the passage of the air over the wing drops the temperature to well below freezing. However, when the temperature is just above freezing, the air over the wing drops to freezing, and ice begins to build on the wing. Ice on the wings causes loss of lift and increased weight. The result is that the airplane goes down. I was in favor of dropping down to 6,000 feet, both to escape the ice and to further reduce the headwind component. The air at 6,000 feet should turn out to be warm enough that ice would not form on the wing. We subsequently dropped down to 6,000 feet and flew there until I could take my next fix.

Meantime, I proposed my solution of increasing power. I did not expect resistance. I thought that everyone would comprehend that such a thing could work. Think of it this way. If the headwind had as much velocity as our true airspeed, we would be hovering, and the only way to make headway would be to increase power. In this case, the headwind was not that strong, but the same reasoning applied. What I had not counted on was the way pilots are trained.

Pilots know that they can make the airplane stay up longer by reducing power. This does two things, it decreases the loss of horsepower due to friction which makes the engines burn less fuel, and, if one has a tailwind, one can use the tailwind to push the airplane to destination. Pilots are supposed to know that, when faced with a headwind, there can be less fuel lost if power is increased. However, they are seldom faced with a situation where fuel is low and there is a strong headwind; so, they forget. Here, in MATS, the old timers tell the youngsters about this, and most of the time there is understanding. But not always. Remember, a pilot has a lot to remember.

I had a dilemma. At 6,000 feet we still had too strong a headwind, and if I did not convince the pilots very soon, we would not be able to reach Bermuda regardless of what we did. Each minute that we burned more fuel at the reduced rate of power, we had a lower ground speed and allowed the headwind to spend more time against us. Chances were already marginal, and we needed to increase power right away. I, for one, did not want to ditch. So I kept badgering the pilots and the engineer, not in a bad way, but in a desperate, logical way. This took about 15 or 20 minutes of valuable time, and I did get a bit pushy. In fact, I was considering getting rather nasty if all else failed.

After about 15 minutes and very carefully showing my calculations, the engineer saw the light. He helped me persuade the second pilot, but the AC, the one who should have known the answer immediately, would not be convinced. It took all three of us working on him for another five minutes before he agreed and increased the power on the engines to what I recommended. It was apparent that he did not understand why we should increase power, but he did understand the urgency that we felt, and that meant to him that we might be correct. Every minute that we had used to convince this AC was one more minute of wasting precious fuel. It was still possible that we would be ditching rather than landing at Kindley.

As the hours passed, the engineer monitored the fuel flow meters and passed the readings to me, the headwind continued, but did not increase. The weather continued to be cloudy and we encountered rain for the next five and one-half to six hours. The range-control chart showed that we were still in the black on fuel, but just barely. We began to break out of the weather with Kindley just ahead of us. The tension had been extreme for all of us, and with things looking better, we were able to breathe more easily. The copilot asked for a straight-in approach, mentioning that we were low on fuel, and the request was granted. It was sunny when we landed with only fumes in the fuel tanks.

We arrived back at McGuire on 27 September 1961. At squadron headquarters after this trip was over, I made some exploratory inquiries to see how many pilots and navigators were aware that an increase in power was sometimes a proper solution to a problem. Surprisingly, many pilots had not thought of it and did not know how to compute it. So I made some attempts in our after-flight bull sessions to bring out the necessity and the method of calculating the power increase. Most of the people were both interested and receptive, realizing that the knowledge could save them someday.

Return to MenuSleeping

There were three men in the squadron who were very short. Two were pilots, and one was a navigator. It was customary for the flight crew to meet the passengers as they stepped into the airplane. The object was to make the passengers feel at ease and confident that their crew was going to take good care of them.

Normally, the flight crew consisted of those who are available at the time, and height is of no consequence. But on one flight the three short ones were together. During the passenger boarding routine most of the passengers seemed a little astounded at their crew but were not too concerned--except for one lady who refused to ride on the aircraft with "those kids". After that, a rule came down that only one short man could be on the crew at the same time. Actually, all those guys were extremely capable, and it was a pleasure to ride with them.

On 6 Nov, 1961, I was part of a basic crew with one of the short pilots who looked like Doogie Houser except he was shorter. He was very congenial and a good pilot and seemed to be proud of the fact that he sat on a pillow to see over the instrument panel. This was another "pony express" flight. We stopped first at Birmingham to pick up troops and then flew to Harmon where we crew-rested. We took off with a different airplane and flew to Prestwick and then Rhein-Main. The rest at Rhein-Main was brief (only half a day) before taking off with the same airplane on the 9th.

We landed at Prestwick, spent the necessary time on the ground, climbed back into the airplane, and had difficulty with number three engine on run-up. So, we went into crew-rest for almost another day, taking off with the same airplane at 5:45 AM local time on the 10th. An hour passed on the way to Harmon, and number three failed completely; so, we turned back to Prestwick and landed after a little over two hours flight time. And we went back into crew-rest.

By this time, we had been awake only a short time, expecting to be working rather than sleeping, the sun was up, there was a whole day ahead of us, and we were slept out. There was no way that we could go back to sleep, but we were scheduled to take another airplane out at 2:00AM local on the following morning, which meant that we would brief at midnight, only 16 hours away. I could not sleep and ate a late dinner (about 9:00 PM as I recall), packed, and prepared for the briefing. At 2:00 AM, we took off again.

The headwind component was rather extreme on our return to Harmon, and the weather was rough, keeping me too busy to even think about dozing between fixes. By the time we entered the Continental Air Defense Identification Zone (CADIZ), I was tired, and keeping to the narrow corridor on the way in kept me stressed. By this time I was working on coffee and adrenalin.

I was the only navigator. We had started at the time when I should have been sleeping. The two pilots could trade off in their duties, but the best I could do was try for cat naps on the way to Harmon, and trying had not been successful. By the time we arrived at Harmon, I had been awake for well over 36 hours. I was too tired to eat, and it was early in the morning local time.

At Harmon, we were quartered in a room for four, and there were three of us, but only one key. I went to sleep, and the two pilots left the room to eat without taking the key. I slept for 15 hours straight and awoke, thoroughly refreshed, and as it turned out, with another day to recover before we took off on the night of the 13th. But for some reason, the pilots were angry with me.

After much inquiring, I found that they had come back from their meal expecting me to open the door, but they pounded and pounded on it and could not wake me. Next, they obtained the key for the room next door which would allow them to open the door between the two rooms and get in that way. But my bed was against this door and it opened into our room. So they pounded on this door to no avail. Finally, the two of them were able to push on the door which pushed me and my bed far enough into the room that they could open it, and there they found me still sleeping soundly. That was the last time they ever took my awakening for granted.

Return to MenuFulfillment

On 23 Nov, 1961, I briefed for another flight to Madrid. Madrid was a very popular destination; so, there three other navigators on board and one extra pilot. Pappy Grant was going to give flight examinations to all three of us line navigators on one mission. This trip was kind of a semi-formal, semi-annual navigator proficiency exam for me, and with Pappy as the examiner, it was likely to be a lot of fun. The crew-rest in Madrid was scheduled to be for three whole days. Madrid was a great place to eat everything from appetizers and wine at sidewalk bars to roast duck with orange sauce at the better restaurants. There were wild strawberries for desert. And there was the flea market on the big hill to buy wonderful things.

During one of our meals, Pappy told us about a mission in the Pacific years ago. It was commanded by an AC who was retiring upon returning home--this was his last trip. So he decided to do something he had always wanted to do. He brought a lot of empty beer cans on board and periodically during the flight he would open the door to the crew compartment and throw a few back into the passenger compartment to the tune of raucous laughter.

I asked what happened to him.

"Nothing", Pappy replied, "What could they do? Ground him? He was retiring--and chances are he only did what all of them had wanted to do for years."

Return to MenuCongo I

There are 905,378 square miles, the equivalent of the area of that part of the United States east of the Mississippi River, in south central Africa, which was once populated only by people other than white--at least some of whom were reported to be cannibalistic. It is bordered in the north by the Ubangi River, running essentially east to west, then turning south to become part of the western border, where it becomes part of the Congo River, and then turns westward once again as the Congo to empty into the Atlantic Ocean. In the late nineteen-fifties and early nineteen-sixties, on the east side lay what was called Uganda and Tanganyika, the border lying partly in Lake Tanganyika. On the south lay Angola and the Federation of Northern Rhodesia.

In the fifteenth century, Europeans were aware of the Congo River, but no major incursions were made until 1876 when Leopold II, king of the Belgians, sponsored the "International Association for the Exploration and Civilization of Africa," which, in truth, meant "Exploration and Exploitation of African Resources by Europeans and Principally Belgians." By August 1877, Sir Henry Morton Stanley had traced the Congo River to its mouth. Subsequently, a committee was formed to study the Congo (Comite' d'Etudes du Haut Congo). As a result of agreements made by Stanley with native chiefs, stations were opened, which led to the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885 recognizing the International Association as a sovereign state. Thus, the Congo Free State was formed with Leopold as sovereign. The name of the Free State was a politically inspired oxymoron as it meant freedom for the European nationals to enslave the true owners of the area, and, of course, the true owners had no voice in the matter. However, this was the proper way for European nations to behave in their race to steal the wealth of the earth by means of other peoples' misery.

In 1889, Leopold bequeathed his rights to Belgium, with Belgium reserving the right to annex the Congo Free State after ten years. However, rather than preparing the natives for annexation, the Belgians continued their exploitation, and the option of annexation was never exercised. Ill treatment of the natives continued and worsened until it came to attention of other nations, and an international commission of inquiry visited the area during 1904-1905. Remedies were introduced, and the state was ceded to Belgium. It was formally annexed to Belgium a year later (1908) and named the Belgian Congo. Abolition of monopolistic trade regulations followed as well as increased care for native health. But new industries and better communications at this point led to increased exploitation of the natives, as was the case in most of the other countries of the world at this time.

Rule of the Congo by Belgium was in the colonial manner, similar to the way the American colonies had been ruled by Britain. The Belgian governor exercised unrestricted power, his responsibility being only the administration of the colonies in Brussels (Belgium). The Congolese population had no means of participating in their own government. In 1957, elective borough councils were instituted in large cities, but this was still far from what is considered self-rule. The police force, called Force Publique, was colony wide, literally an army staffed by Belgian officers, with no Congolese attaining the rank above sergeant.

On 4 January 1959, a large-scale nationalistic outbreak occurred, leaving scores of people dead in Leopoldville. In succeeding months, riots occurred in other major population centers. Fearing a complete revolt, the government in Brussels drafted a program for attainment of self-rule in stages over a period of years. If it had been followed unimpeded, it is possible that this program would have worked. Had it been attempted years before, it might have been timely and productive. Now, however, the Congolese nationalistic leaders demanded immediate independence. With only about 100,000 European nationals living among 14 million Congolese, it was apparent that the Congolese would win any physical confrontations; so, the demand was granted on January 27, 1960.

The formal proclamation was scheduled for 30 June, the new nation to be called the Republic of the Congo. A form of representative government was planned, political parties were formed, and elections were held. But shortly after independence was declared, several adverse events occurred, including the mutiny of the Force Publique, a military intervention by Belgium to protect Belgian nationals, and the arrival of a United Nations force in an attempt to keep the peace. Strife between opposing forces in the new government threatened to lead to civil war with nations of the east and west joining in the conflict.

The population of the Republic of the Congo as of 30 June 1960, consisted of 14,150,000 people of which 110,000 were Europeans, about two-thirds of whom were Belgian and the majority of the balance British. By the end of 1960, there were only 45,000 Europeans, over half of whom were in the District of Katanga, located at the extreme south of the Republic. Although some of the Europeans had escaped by leaving in a timely manner, many had stayed and had been killed in the fighting, disliked by many Congolese in all of the Congolese factions involved.

In 1960, in the Congo, MATS participated in the largest airlift operation since the Berlin airlift of 1948. By early August of that year, the United States Air Force in Europe (USAFE) and MATS had transported approximately 4 million pounds of equipment and supplies to 9,000 U.N. troops in this country, and had taken out 2,500 refugees.

The Africa of the early nineteen-sixties was not the Africa of the late nineteen-nineties. At that time, there were no satellites to map the area, and much of it was uncharted rain forest, broken by poorly charted mountains, streams, rivers, and lakes. The only major attempt at mapping was being done by U. S. Air Force C-130s in an operation that seemed endless in its magnitude. In the rainforest of the Congo, which comprised most of that area, the tribes still lived, resentful of the encroachments of civilization brought by the whites, who, when caught, were often invited to dinner as the main course.

The detribalized Congolese generally lived a life similar to that of slaves in the deep south of the United States during the early eighteenth century. Those that were better off were only able to rise to the level of lower management or sergeants in the Force Publique. Their usual role was similar to the "slaves" of our industrial age who barely earned enough money upon which to live and who worked for long hours each day. In the cities, their work places were factories, and outside the cities, their work places were plantations and mines.

The Belgian government was in favor of keeping the Congo as a colony, if not in name, at least in fact. It was a major source of raw materials for Belgium, a critical part of the Belgian economy. The Belgian nationals in the Congo were varied in level, but always above the Congolese. A few were major owners or executives of industries. Some were high or middle management. And some were merchants, hotel owners, restaurant owners, or other types of businessmen. In almost all cases, the European nationals were of classes that would lose if the status quo were severely altered. Their occupations, houses, business holdings, and life savings could be lost if too much change were to occur too quickly. Yet, they had not prepared the natives for independence. The natives were still largely uneducated insofar as managing their own industries and their own government.

Sporadic fighting continued throughout 1961 in various areas. The European nationals who remained were torn between a desire to keep their holdings, which were often substantial, or to start all over again with nothing, as refugees living in a relatively strange country. Most had lived in the Congo for their entire lives as colonials, and everything they owned, real estate especially, was there. Even the threat of imminent death often failed to dissuade them from leaving. They constituted a strong political voice for maintaining the status quo as much as possible.

The violence might possibly subside, and it was never everywhere at once; so, many of the European nationals stayed, and some of them died for it. They and the Belgian government were largely in favor of United Nations intervention, while most of the natives were in favor of no intervention of in kind whatsoever.

If the Congolese uprisings were to continue to the point of nationalizing the industries, Belgium would lose money from mines exporting diamonds, cobalt, tin, manganese, iron, lead, zinc, copper, silver, gold, radium, and uranium, and from plantations producing oil, rubber, hardwood, and other woods. In addition there would be loss of funds from the export of Cinchona bark, ivory, derris, skins, pyrethrum, cassava, bananas, maize, peanuts, cotton, rice, yams, and sorghums. And all of these industries were made possible by the use of cheap native labor.

If the detribalized Congolese could rid themselves of the foreign yoke and learn to manage their own industries and government, they would gain the wealth back that had been stolen from them. And if the tribal Congolese could rid themselves of foreigners, their own way of life might continue for a longer time before their forests were cut down and their waters hopelessly polluted.

In January 1962, the central government of Premier Cyrille Adoula successfully thwarted the secession of Orientale Province. The federal Chamber of Deputies, on 8 January, directed Antoine Gizenga, federal Deputy Premier and leftist political leader at Stanleyville, to return to Leopoldville to answer accusations of alleged secessionist activities. On 13-14 January, Gizenga's forces attempted to seize military control of Stanleyville, but they were defeated by troops loyal to the Leopoldville regime. The central government immediately censured Gizenga and dismissed him as Deputy Premier.

It was "revealed" on 17 January that Congolese troops supporting Gizenga had murdered twenty-two European Catholic missionaries at Kongolo in northern Katanga on 1 January. The alleged murderers were captured later in the month by central government troops. The United Nations forces placed Gizenga under "protective custody" on 20 January and flew him to Leopoldville, where he was arrested and imprisoned by the central government. This action did little to inspire trust in the United Nations, as if there had been very much before, and with Gizenga in custody in Leopoldville, there was danger of further violence either to liberate him or to vindicate him. Although it may never be proven, it was apparent that this action of the U.N. forces, the intervention in Congolese affairs by fraudulently acquiring Gizenga so that he might by imprisoned by his political enemies, was premeditated.

I believe that it was the premeditated duplicity of the United Nations that caused a MATS crew to be briefed at 11:25 AM on 19 January, to fly "as directed," returning on or about 31 January 1962. Obviously, there was foreknowledge that Gizenga would be imprisoned in Leopoldville in the very near future and that United Nations troops would be needed there to prevent his release by his followers. Otherwise, our take-off on the 19th would not have been necessary.

The people of the Congo were mainly Bantu and Sudanese tribes, with small minorities of Nilotics, Pygmies, and Hamites. Four main languages were in use with several hundred different dialects. In the large cities, the principal language used for business was French. Although many of the natives had been detribalized, many of the tribal traditions continued. The failure of Belgium to educate the population in representative government, the example of double standards (one for Belgian nationals and another for Congolese), and oppression of Congolese via the Force Publique, had only increased the Congolese hatred for all whites. These things, the reluctance to involve whites in the conflict when blacks were available and the increasing distrust of the United Nations forces by the Congolese, led to the United Nations' use of black troops rather than white troops to enforce the peace. And in the ensuing years, black U.N. troops were flown into the area while those whose contribution was complete were flown out. These troops were brought in largely from or through Nigeria and Ethiopia, via military aircraft of which a large part were from MATS.

The aircraft that left for the Congo on 19 January 1962, had an augmented crew but no females and no additional crew members. The crew wore class "A" blues as usual but carried olive drab flight suits, plenty of clothing, personal firearms, and personal survival kits. The aircraft was a 1953 model, and the passengers looked like any other group of passengers. The first portion of the flight was routine, from McGuire to Lajes and Rhein-Main.

After a very brief rest at Rhein-Main, our crew departed for Wheelus AFB, Libya, taking another aircraft, a 1951 model C-118, which meant that it had a driftmeter. A driftmeter is a device seldom used for flying over the ocean, but excellent for flying over land devoid of radio navigational aids, and Wheelus is located at the top of the Sahara Desert, which is an area devoid of any navigational aids. We Left at 0835Z (9:35 local) which made for daylight flying in some of the most beautiful country in the world.

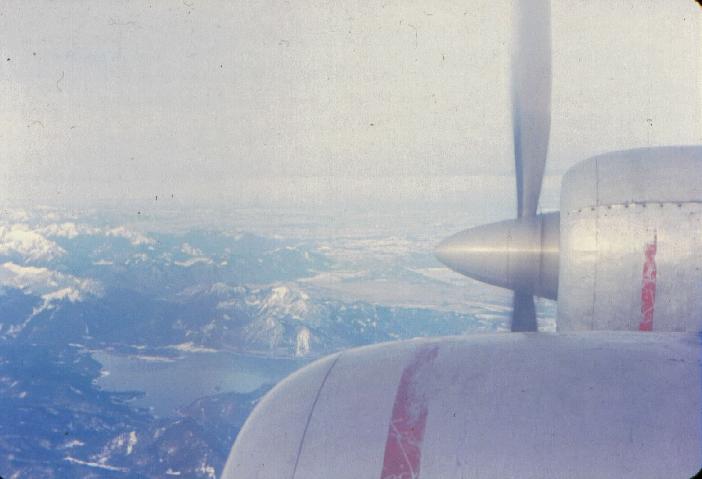

On the way to Wheelus we passed over the Swiss Alps, covered profusely with snow, a lovely view of jagged peaks and small towns nestled in valleys between them. I spent much of my time looking out the window and taking 35mm slides, this being the first, and possibly the last time I would see them.

Later, we flew over Naples, Italy, with Mount Vesuvius nearby, and again I took several shots with my camera. The shot I took of Vesuvius was and is spectacular, showing the coast with the town right on it, the volcano in the immediate background with the crater on top, a hazy valley behind and more mountains behind that, until everything blends into a haze that obscures the horizon.

Vesuvius

I took some other shots of a lighthouse off the coast of Tripoli and the coastline itself as we descended to the Airfield.

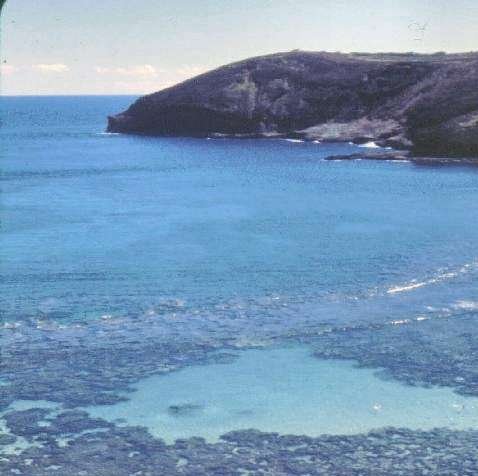

Lighthouse

We refueled at Wheelus, green as an oasis with white buildings, and began the next leg of the journey which was across the Sahara to Lagos, a coastal town at the south of Nigeria which was the federal capital. We arrived at Wheelus at 1345Z (2:45 PM local) and took off at 1610Z, leaving the clouds that were scattered over Europe and the Meditteranean for clear air except for blowing sand that was sometimes visible far below.

The Sahara Desert is a sea of drifting sand; so, hot in the daytime that the aircraft at altitude was warmed. Even from an altitude of 15,000 feet, it stretches for hours from horizon to horizon. Below, there were some trails made by caravans, which were not well defined enough to use as navigation aids. Occasionally, rock outcrops were seen which could serve as guides for the driftmeter but were not found on the map and, thus, could not be used directly to fix the position of an aircraft. There were no radio aids, LORAN is useless over land as is pressure pattern navigation, and the only celestial LOPs had to be taken from the sun. Even clouds are seldom ever seen and smoke is not present; so, wind velocity and direction could not be determined from these. In short, it was one of the most challenging of places for navigators, requiring something like extra sensory perception for any accurate idea of one's position.

We flew for eight hours on this leg of the trip, most of which was over the Sahara. Toward dusk a radio from Nigeria allowed us to discover how far we had erred from course, and we were able to make any necessary corrections. We had not done badly as I recall, in spite of the difficulties, and in the descending darkness below we knew that we were once more over a land that was gradually turning from sand to rainforest.

Nigeria was a British colony and protectorate of West Africa. It was divided into Northern, Eastern, and Western regions with capitals, located at Kaduna, Enugu, and Ibadan, respectively, and comprised 27 provinces, including the former Lagos Colony and, for administrative purposes, the United Nations trust territory of British Cameroons. The basic racial strain in the south and throughout most of the remainder of Nigeria was the Congo-type Negro. Although Mohammedism is the predominant faith in the northern and western regions, the remainder of the population is largely pagan.

After we landed and refueled, the United Nations troops were marched up to the aircraft, resplendent in their army green uniforms and bright blue berets. Their faces were also very resplendent--much more so than ours--because they were decorated with designs made of scar tissue, the product of many hours of patient and artistic cutting with knives and rubbing with salt or ashes to be certain that scar tissue formed. Each black face was unique in its designs, each mouth had teeth that were filed to points and, admittedly, the effect was fearsome. The rumor was that these people either were currently, or had been, cannibals, and the rumor may well have been correct. As they filed on board and sat in our rear-facing seats, I watched them without making direct eye contact and noted that they seemed to be without fear or even minor anxiety about the coming flight. And on the way to Njili, they slept as anyone would who had been forced to march and climb into an airplane in the wee hours of the morning.

We did not have diplomatic clearance to fly over French Equatorial Africa, and navigation was better over the ocean; so, we flew just off the coast until we came to the western tip of the Congo and then turned east to reach Njili which was near the edge of a very large veldt near some small mountains (large hills?). The mountains were sparsely covered with vegetation that was mostly at the lower levels.

The airfield at Njili was paved and had some small buildings as well as some larger hangars at the edge of it. There were a lot of DC-3s parked on the field as well as a few small aircraft. The people there were not used to servicing C-118s, and our people were needed to supervise. The language barrier was not helpful, and the process took some time. We were tired, hot, stinking, and rather moist (in fact wet) with perspiration, and if it had not been early morning the perspiration would have been worse. The one very pleasant thing about this place was the lack of paperwork since there was no base operations to report to or to give us information.

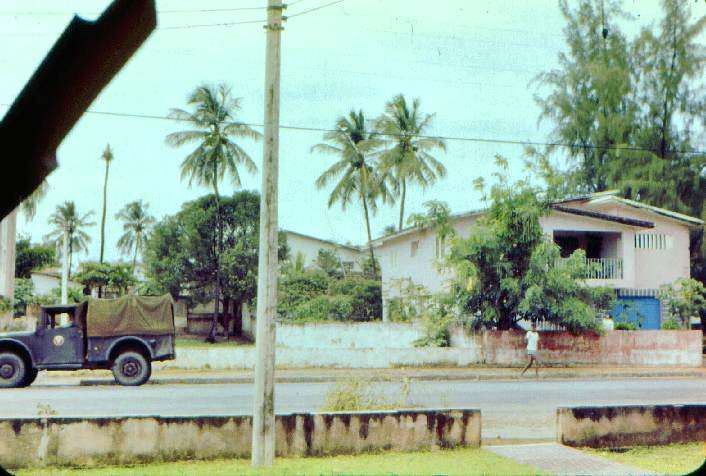

Njili

A truck of the land rover type with an open back, covered only on top with white canvas, came to pick us up. We threw our bags on board and climbed in. The breeze that whipped by as it bounced along was pleasant. Occasionally, a native woman would be seen walking along the side of the road, dressed in a loose white or pastel-colored garment, her head shaved with a cloth over it. This seemed the best sort of dress for the climate. Away from the airfield, the veldt was completely covered with tall grass of a golden color, except by the road where small drainage ditches were lined with short green grass. There were a few small trees, hardly more that shrubs with green tops spread out like cirrus clouds on a trunk devoid of limbs. These trees were scattered about a sea of golden grass. There were no animals visible.

As we drew nearer to Leopoldville, the land became one of gullies which seem to have been made by many rains, small ones being tributaries to larger ones. There may have been water in the bottoms of them, but we could not see it from where we were. They were lined with dark green vegetation and areas of what appeared to be grazing land lay in between. The view was rich and lush with the various elevations and the colors of green with some shades of brown where the soil could still be seen at the sides of the gullies. When we reached a higher elevation, we could see miles and miles of rolling hills in the distance with alternate areas of grass and groves of small trees. When we arrived at our quarters near the University at Leopoldville, the landscape was even more green with less brown and gold.

This land was very large and very beautiful without very many humans or domesticated animals. We could see for miles and miles and not discover anything but vegetation. Perhaps there were animals out there, but they could not be seen. The University was modern and large, white multi-story buildings with exterior walls that were mostly windows, looming up in stark contrast to the land around it.

The University

Having arrived tired in the early morning, waiting for the aircraft to be serviced, bouncing along in a truck for 45 minutes, and then showering before sleeping, we were ready for bed. But it was not so easy, because the day was growing warmer, the light brighter, and we needed to eat. The last decent rest we had experienced was at home. The rest in Rhein-Main was very brief, not truly allowing time for sleeping, and it was the same here in Leopoldville. We were being allowed only 13:25 hours from arrival at Leopoldville to departure. We could manage with it, but someone was certainly in hurry to have us pick up the next load of troops. It was now the 22nd, which means that Gizenga had been in custody for over a day.

At midnight, we left Leopoldville in the truck and took off from Njili at 0335Z. We took on another load at Lagos, this time able to see the countryside and the buildings. There did not seem to be an appreciable difference in the vegetation at Lagos from what we saw at Leopoldville, but the land was very flat.

Njili

The continent, from this side at least, was very green. We arrived at Leopoldville again, this time in the evening, and managed to get some solid sleep until we roused for an 0600Z departure.

Again up the coast, overflying Nigeria, and into the Sahara for another warm day; we arrived at Wheelus after a long twelve hours of flying, only to refuel and fly for another ten hours to Lajes in the Azores.

Wheelus

The lack of passengers or cargo allowed for more fuel and more time enroute; so, pilots and navigators took turns managing the flight, and caught up by taking short periods of sleep in the crew bunks on the airplane. At Lajes we had time for a good meal, and I managed to get a haircut, this being my favorite place east of the U.S. for having my hair cut. This crew-rest was longer but in daylight, and at midnight we were in the air again for an 11:30-hour flight to McGuire. We had left on the 19th and we arrived home on the 26th with 77:55 hours of flying time for the entire trip.

Return to MenuCharlie's Partner

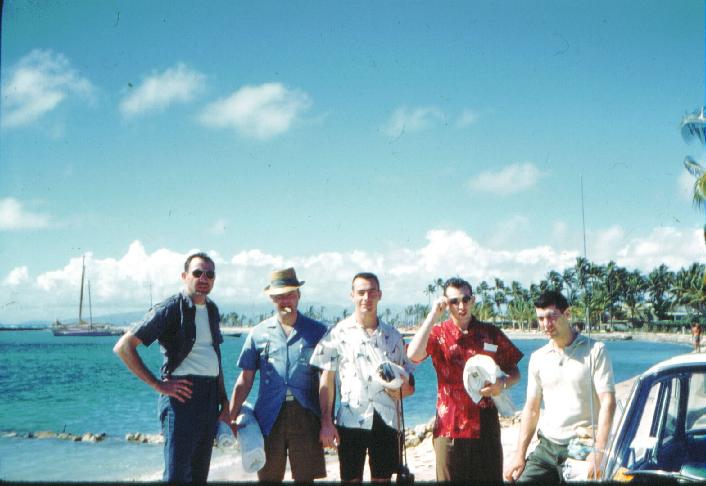

On 28 January 1962, a crew of which I was a member was briefed at 2:25 local time. It was a basic crew of five men going to the Pacific area for another "pony express" run. Initially, I recall, we were teamed up with another basic crew. We were expecting to be gone for a much longer time than usual and had briefed our wives on the bills to be paid and other tasks that they would do alone during our absence. We were to reach our predetermined station via deadheading on a C-124. Upon arriving at Oahu after several stops enroute, we "rested" for three days.