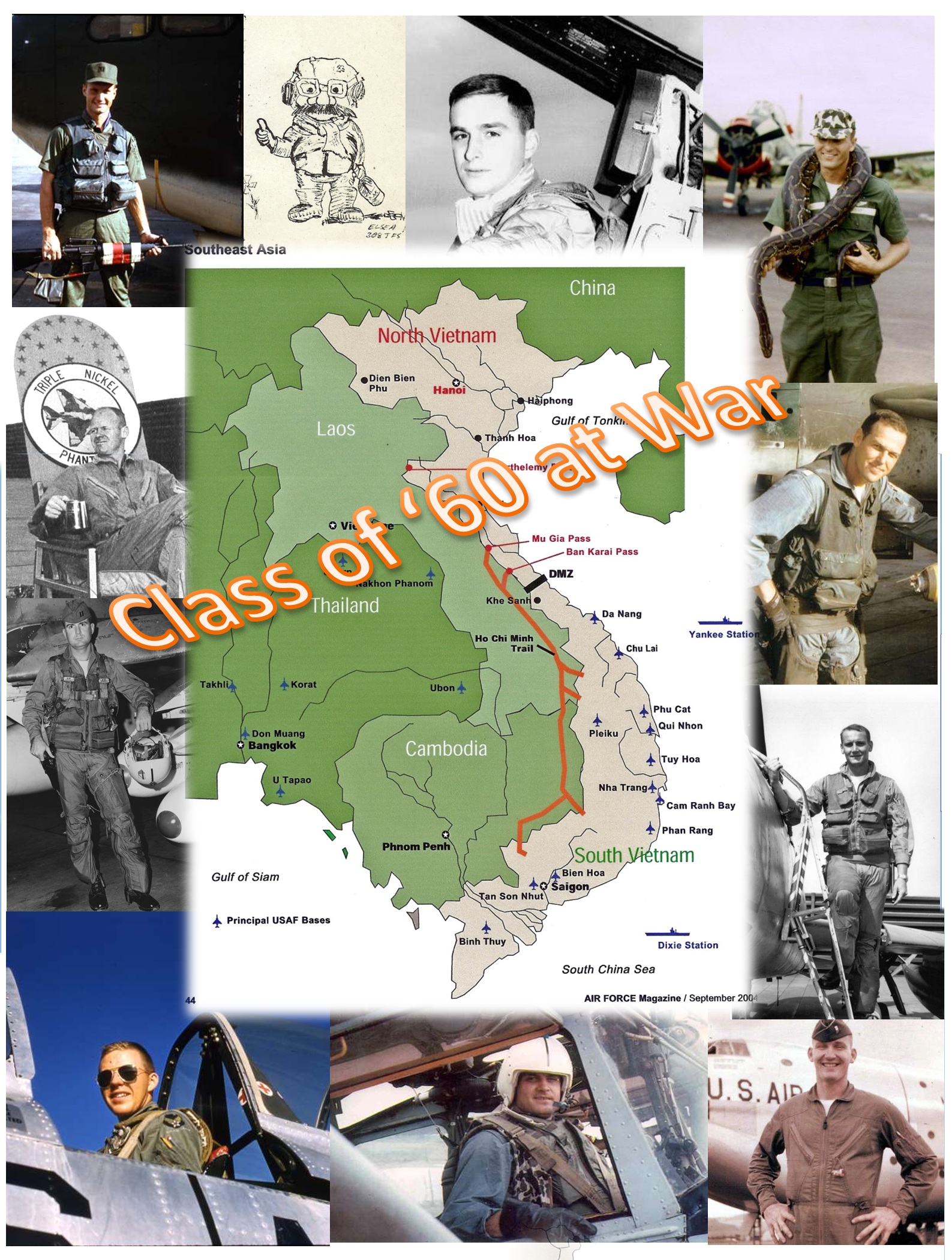

Class of 1960 at War

The fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975, marked the beginning of the end of USAF combat operations in Southeast Asia, more than two decades after the fall of Dien Bien Phu and the beginning of USAF assistance to South Vietnam. By the end of 1976, Laos and Cambodia had also fallen to the communists and the last USAF and Naval units had departed Thailand--thus concluding almost 15 years of continuous Class of 1960 participation in what we generally refer to as the Vietnam War.

What follows is a rough chronological narrative of the wartime experiences of some of our classmates. Some 55 classmates actively participated in this Class War Stories project and the full text of their stories can be found on the CD that accompanies this book. Several of the longer pieces can also be found on the Class website. Most of the stories pertain to the air war in SEA, but since the Cold War was in full swing during our early years of service, we also have a few stories relating to that topic and to other post-Vietnam adventures. Many of our class were cited for heroism in battle; some of their stories are included in this history. One of our classmates, Don Stevens, was cited for extraordinary heroism and awarded the Air Force Cross and the Jabara Award. Of the 152 members of the Class of '60 who served in SEA, a total of twelve Silver Stars were awarded to nine different individuals: Howie Bronson, Ed Haerter, RG Head, Mike Hyde, Ed Leonard (4), Dick Meyer, Tom Seebode, Don Stevens, and Dave Wiest. The statistics on other awards for valor and achievement (DFC, BS, PH, AM, etc) can be found in the Statistics section of the Yearbook. Since most of our stories were provided by rated pilots, except where mentioned otherwise, the named classmates were fixed wing or rotary wing airplane drivers.

Perhaps the apogee of the Cold War was the Cuban Missile Crisis in October of 1962 and a few of our classmates have recorded their memories from that dangerous time when US forces went to Defense Condition (DEFCON) II. John Kuenzel was assigned to a KC-135 crew at K. I. Sawyer AFB in Michigan's Upper Peninsula: "There was no hint of an international crisis at the squadron level. The initial indication came upon assuming ground alert status on a Monday morning. By noon we were airborne enroute to Spain where we joined a tanker task force assigned to refuel B-52s flying 24-hour airborne alert sorties from the States. We flew three sorties every other night. I do not recall the exact duration of the crisis, but the tension peaked on Saturday night. The Soviets must have agreed to remove their missiles over that weekend in October. Our crew flew three sorties that night. There were reported MIG sightings (never verified), and large ship movements reported over the radio. After that, in clear text, an authoritarian voice announced over the HF (long range) radio directing us to report any unusual sightings, hence avoiding any delay. I never discovered the identity of that speaker, but he clearly had command authority to change the world that Saturday night."

Paul Vallerie's first assignment after graduation was as a Deputy Missile Crew Commander in the 567th Strategic Missile Squadron at Fairchild AFB outside Spokane, Washington: "Our missile was a liquid propellant one called the Atlas E. The Atlas E was in the 'coffin' configuration, which means that the missile was lying flat in a concrete bunker and was only about 100 feet from the launch console. Each missile back then had their launch crew right next to the bird. Every tour of duty, which lasted 24 hours on site, we had to physically inspect the missile and the 1.2 megaton warhead. The fuels were hypergolic, which means they exploded when mixed. So we had to insure there were no leaks in the pipes that lead from the storage tanks to the missile. Scary as hell for the first couple of tours, but then you got used to it. It took approximately 10 minutes to raise, load and fire the missile." "When the crisis hit, we were all recalled to the base for a special briefing. The Command Post at Headquarters SAC contacted our Command Post and we heard from the lead controller what was happening. We were put on six-ring alert. This all sounds great except that, as a bachelor, I was literally trapped in my apartment, even though Ralph Miller lived just two floors above me. I learned a year or so ago, when the squadron records were released, that our missile squadron was the only missile squadron in the US that could be targeted toward Cuba. The other Atlas and Titan outfits were too close and could not be programmed against Cuban targets. Our missiles were. The Cuban Missile Crisis lasted 44 days. We were about ready to do anything to get out from under that six-ring alert."

Howie Whitfield (USMC) got somewhat closer to the action: "In October 1962, flying the Sikorsky single-engine UH-34D, I deployed aboard a helicopter carrier, USS Iwo Jima, out of San Diego on the Cuban Missile Crisis. Our task force went through the Panama Canal and cruised back and forth off Haiti prepared to assault Cuba if necessary. Fortunately, it wasn't necessary, as based on intelligence briefings we received; it would have been a very bloody affair." J.P. Browning was assigned to Myrtle Beach AFB flying F-100s: "During the Cuban missile crisis, we deployed to McCoy AFB in Florida where we flew armed air-to-air missions out over the Gulf of Mexico between the US and Cuba. We sat alert with airplanes armed with conventional ordnance, and on more than one occasion we felt we were minutes from launching."

Jerry de la Cruz

The Advisory Years (1961-1964)

The story of our class's participation in struggle against communist oppression in SEA even predates the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. In 1961, in Thailand, the USAF was quietly supporting low profile flight operations from Takhli RTAFB into Tibet and Laos. Ed Haerter was with the 774th Troop Carrier Squadron (TCS) at the time and deployed to Thailand and subsequently Vientiane, Laos, as a C-130 navigator. "During this deployment, we dropped supplies, consisting of arms, ammunition, etc., to allies in the Plain of Jars region of Laos. During several of these flights, we were fired upon and our aircraft received hits from small arms fire. We were told to keep quiet about the entire operation and our flights were logged as operational, not combat. I believe that marked the first time US aircraft were used in combat operations in SEA." A year later, more than two years before the United States was "officially" involved in the Vietnam War, Charlie Folkart was flying F-100s for the 430th TFS, which was deployed to Takhli on a contingency basis due to insurgent activities in Laos. This was to be the first of four assignments in the AOR for him. It should be noted that SEA was not the only hot spot that welcomed our class. Ken Werrell recalls Brian Deem telling him that he, Brian, flew as a navigator in the Congo Airlift of 1961, the largest airlift since the Berlin blockade. Flying into Leopoldville where troops and their gear were offloaded, Brian thought he saw fireworks, only to be informed that what he was seeing was AAA. [Ed. Note: This may have been the first instance of one of our classmates encountering hostile fire.]

This first phase of the Vietnam War, the Advisory Years, began in December, 1961 when the US aircraft carrier, the USS Core, arrived in Saigon with 33 helicopters and 400 air and ground crewmen assigned to operate them for the South Vietnamese Army, and U.S. pilots start to train and fly support missions with the South Vietnamese Air Force. This event marks the first large scale participation of U.S. military "advisors" in South Vietnam's struggle against communist forces. Dave Sweigart, by all accounts the first in our class to embark on this frustrating and challenging adventure, was in Da Nang in Feb '62 for 30 days and in Saigon for 179 days beginning in Sep '62, flying combat support missions in C-123Bs with a TDY rotation out of Pope AFB called "Mule Train." In May 1963, Andi Biancur was among the early USAF deployers to Bien Hoa AB as a B-26 pilot with Det 2A of the 1st Air Commando Wing, code named "Farm Gate." Ken Alnwick joined him there in June and was assigned to fill a slot in the RB-26 program. Ken recalls that "We were supposed to be in Vietnam as advisors, and to preserve this fiction, we flew with a Vietnamese airman 'observer' in the jump seat behind the copilot/navigator position. This was a cruel farce. The 18-year old airmen who flew with us were barely literate and spoke virtually no English--and had absolutely no access to either radios or flight controls. Their only role in life was to provide a cover story for us in the event we all died in a crash."

Don Wolfswinkel & Andi Biancur

the air and the remainder of the aircraft tumbling out-of-control and heading for the ground. I yelled for them to get out, but, of course, it was impossible because of the adverse 'Gs' and lack of time. I immediately broke off the attack and called Paris Control (the tactical control agency) to report the incident." A few months after that incident all the aircraft were grounded--only to return to the fight five years later as the A-26 which, with reinforced wings and other upgrades, was a far more capable aircraft.

Les Hobgood

J.T. Smith

On 24 October, 1964, the C-123 airlift mission took our first casualty of the war, when Val Bourque became the first USAFA graduate to die in combat. Val's last flight was a two-ship airdrop at a Drop Zone (DZ) just south of the Cambodia-Viet Nam border. Val was adamant that he command the lead aircraft, as it was to be his last flight before returning to the States. On the approach to the DZ, Val's aircraft was riddled with 50-caliber fire, fatally damaging his aircraft, which crashed inside Viet Nam. Major Byer, in the number two aircraft, was able to abort his own drop, and he reported the shoot down.

Not long thereafter, Earl Van Inwegen was assigned to the 309th Air Commando Squadron at Tan Son Nhut AB and got his in-country checkout in the C-123 by the same Major Byer. In his words, Van "found flying the C-123 a fantastic experience--going into unprepared airfields, airdrops and night flare missions in country, interspersed with two two-week tours in Thailand'flying in-country support, trips to Clark, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Kuala Lumpur'all in all a great experience, including an exciting mission into Du Co where we escaped with no hydraulics, both nose wheels flattened, 24-50 caliber holes and part of our left aileron damaged by a mortar that landed nearby."

Howie Whitfield

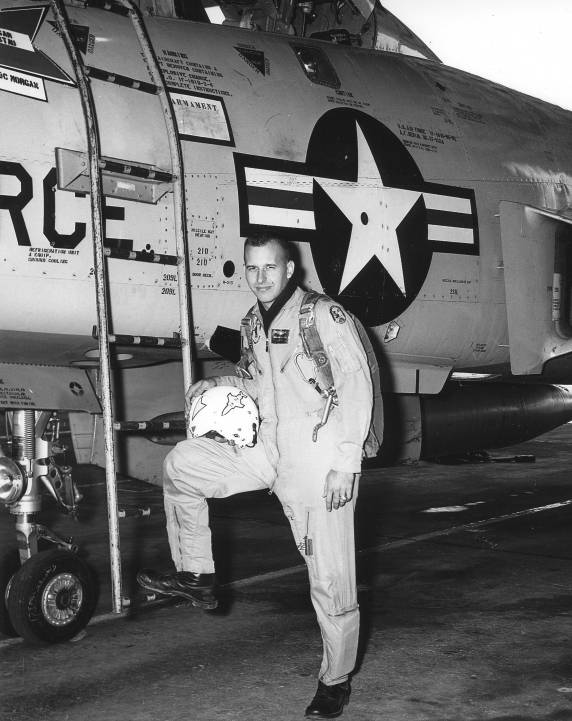

1964 also saw the introduction of USAF jet fighters into the fray, in response to what is now known as the Gulf of Tonkin Incident when three North Vietnamese torpedo boats attacked the USS Maddox on August 4, 1964. Ron Yates and Sid Newcomb were among the first jet fighters to respond. Flying out of Clark AB, PI, Ron Yates' F-102 was the third US jet to land in Vietnam that night and Sid Newcomb was one of four F-102s deployed from Naha AB, Okinawa, to stand alert in Saigon as part of the reaction to this attack. Their mission was to defend against a potential threat from Soviet-made bombers from the North. Sid flew 12 sorties and returned to Naha. Russ MacDonald was also one of the follow-on Naha F-102 deployers. He would later return to the theater for two more tours.

For the next 21 months, Ron spent most of his time rotating between Da Nang, Saigon, and Don Muang, Thailand and Clark AB and flew 100 combat missions. Ron was heavily involved in developing air-to-ground tactics for the F-102, which had limited effectiveness in this role, as it had been designed for air-to-air combat. His most harrowing experience, however, came not in the air but on the ground, when the Viet Cong launched a sapper attack on his alert facilities at the end of the runway at Da Nang. After a fierce firefight the USMC detachment there drove off the attack. As Ron recalls, 'On that night, I was VERY glad for the small arms training we had at Buckley our doolie year! The next morning, the 7th Air Force Commander arrived with his aide, George Pupich, to inspect the damage. My face was pretty bruised from rocket concussions and George persuaded the General that I was too ugly to remain in-country. So, I was sent back to the Philippines to recuperate."

Years of the Offensive (1965-1968)

Ron's 21 months bridged the transition from the Advisory Years to the Rolling Thunder attacks on North Vietnam (March 1965) and the buildup of US forces that would last through 1968.

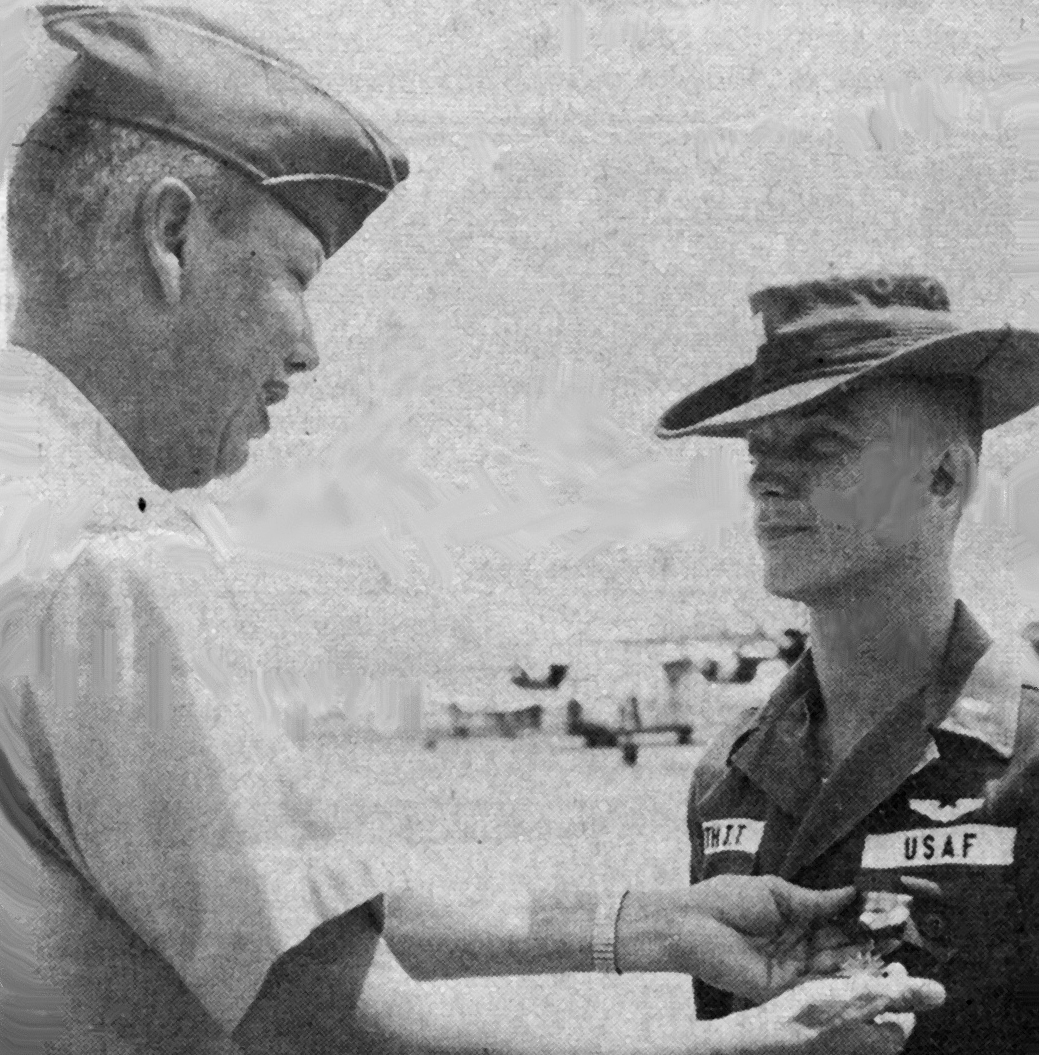

In 1965, George Pupich had two jobs in Vietnam--Aide de Camp to Lt. General Joe Moore the Commanding Officer of 2nd Air Division (his real job), and an A-1E slot in the 602nd Air Commando Squadron (the job he relished). In his aide capacity, George worked a lot with former AOC Ken Tallman, General Westmoreland's Chief of Staff, and was instrumental in having General Westmoreland present Howie Bronson the Silver Star for his work as a FAC. He was also present when RG Head came in "glassy-eyed" from an early morning mission to a memorable location'Khe Sahn. George got to see a great deal of the "inside" activity pertaining to the war by being Moore's aide, but he deemed that that was a mixed blessing: "I became very disenchanted with Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara and President Lyndon Johnson. Those observations led me to resign my commission exactly one year after I completed my RVN assignment."

Ed Nogar

Another 1965 IV Corps veteran is Tom Seebode, who racked up 576 combat missions supporting a US advisory team and ARVN forces in the My Tho area. During his tour, Tom had two airstrips overrun by VC, once losing his Birddog in the process, and for several months had to FAC from the rear seat of an Army L-19 until a replacement O-1 could be found for him. By 1965, the VC had learned that the key to keeping fighters at bay was to neutralize the FACs. On Tom's Silver Star mission, he dueled a VC .50 caliber gun with Willy Pete (White Phosphorus) rockets and saved many soldiers' lives by directing accurate fighter support against entrenched VC forces. Despite his many combat sorties, Tom claims that "the 10-mile drive from the advisor's compound to the primitive ARVN air fields was the most hazardous part of my day."

In 1965, Tony Burshnick joined the ranks of McGuire '60 grads that traded MATS patches for a more exciting lifestyle, flying C-123s from Da Nang and Tan Son Nhut. Tony vividly remembers flying "Ground-Controlled Approaches into remote dirt strips guided by a guy on the ground with a hand-held radio and a good set of eyes." His most extraordinary mission occurred when his C-130 was sent on a fire-bombing raid into the Bo Loi woods northwest of Bien Hoa. All C-123s in Vietnam were assembled to drop pallets of fuel drums with flares for fuses to burn the VC out of the defoliated area. As Tony recalls: "We made our way back to Tan Son Nhut, and, after landing, watched the fire take on the Viet Cong. At the same time we also watched tremendous rain clouds starting to form. Soon the area was blanketed with thunderstorms, which in the end probably put out most of the fires. We never did get a body count." Tony also had occasion to meet classmate Alan Sternberg, who had left the Academy due to illness, but had worked his way into the combat zone by volunteering to be the head of the USO in Saigon. Also in Saigon at that time were Roy Jolly and Chuck Diver.

CT Douglass was flying Birddog FAC missions further north around the Pleiku plateau at about the same time, supporting the ARVN II Corps and five Army Special Forces A Team camps. One camp, Plei Me, came under attack and the fight eventually became the Battle of the Ia Drang Valley. CT was attached to the 1st Air Cav until the battle's end. On Christmas Eve 1965, CT had a surprise Christmas present: "I had just returned from an afternoon mission and I dropped in for a drink in our shipping-container hooch bar to relax, when, lo and behold, my old Doolie Training roommate, Dave Bradshaw, strolled in. He was an Army Special Forces Captain passing through Pleiku on his way to join his 'A team' up in Kontum. The next morning I flew him up to Kontum and dropped him off. A couple months later, I heard that he had been killed up there in a firefight, and have not heard about him since. During my seven months in-country I was always hungry, tired, and scared and amazed at the casualties we were taking, but challenged and excited that I was 'making a difference.' It was lots of responsibility--the PERFECT combat assignment!" [Ed note: Fact-checking this story, we discovered that CT had picked up a bad rumor. Dave Bradshaw is alive and well and living in Texas.]

Ken Alnwick on the left

Jim Fey was an F-100 pilot who had been selected to attend MIT to fulfill his dream to teach engineering at the Academy. He deployed to Da Nang in the summer of 1965 and returned to England AFB after a 164-day TDY in theater. As he was preparing to return to Vietnam with his wing, he was killed in a night flying accident on an unfamiliar gunnery range during inclement weather.

Bill Gillis served the first of his two Vietnam tours as a C-123B Air Commando pilot at Da Nang SVN. On his first in-country mission, in January 1966, his aircraft was badly shot up in the same place where Val Bourque had gone down over a year before. "From Da Nang, we flew five to seven missions a day in all weather, many into small outposts in rugged mountainous terrain. We took ground fire on roughly 95% of all the missions we flew. There were many interesting flights, especially the time leaving Khe Sanh when one engine began to fail, causing us to keep it running, despite the imminent risk of engine fire, to get through the Karst with a load of wounded Marines and indigenous troops. We landed at Quang Tri with one engine still working and a C-130 on the runway. Yes, we had holes (battle damage) on almost every flight as we flew into the small dirt strips. On one flight, the crew chiefs repaired over 200 flak holes before the next day's flights."

Charlie Thompson was flying C-123s out of Saigon that year and also performing duty as a controller in the Transport Mission Control Center, logging back-to-back 12-hour days. On his days off, he would relax by flying combat sorties into remote mountain-top dirt airstrips.

By 1966, the war had definitely moved into a more 'conventional' phase, and the, US commitment had grown to some 385,000 personnel (up from some 16,300 'advisors' in 1963), not to mention additional forces from South Korea, Thailand, Australia and the Philippines. Rolling Thunder, the air war over North Vietnam, had resumed after a month long hiatus (Brian Kaley had provided KC-135 refueling support to that operation in 1965). Essentially, the Air Force was fighting four wars simultaneously. In the North the US was attacking a tightly controlled list of carefully prescribed and often highly defended targets in an attempt to get the North Vietnamese to agree to some sort of political settlement. In northern and southern Laos we were conducting interdiction campaigns against NVN forces moving along the Ho Chi Minh Trail. And, in South Vietnam, we were engaged in an all-out war of attrition against the Viet Cong'including B-52 Arc Light bombing raids. In concept, the US would conduct high intensity air and ground operations to provide a shield behind which the Vietnamese Armed Forces could regroup and rebuild as the Americans and their allies eroded the communist's ability to continue the fight.

1966 also saw a steady influx of fighter'qualified classmates into the war zone, including John Peebles, Russ MacDonald, George Elsea, DK Johnson, Sid Newcomb and Sam Waters. John Peebles flew F-100s out of Phan Rang and rang up some 300+ sorties. On one night mission south of Saigon, he and his wingman came to the rescue of two downed Army choppers by dropping napalm as illumination to help them hold off the VC until help could arrive. Eight years later, in the only bar in his small home town, John found himself sharing a beer with one of the soldiers whose life he had saved.

Russ MacDonald flew F-4Cs out of Da Nang AB, RVN from June, 1966 through December, 1966: "We flew a month of nights and then a month of days, etc. At night, we interdicted in and above the DMZ, against hard-to-see targets Illuminated by flares. Keeping away from the mountains and other aircraft (no lights) could be sporting. The best part was that the North Vietnamese rarely could really see us. During the day, we flew interdiction missions in the same area and in Laos, but the main work was escorting F-105's into the far north."

Sid Newcomb returned to the war in August as an F-4C pilot in Robin Olds' 8th TFW at Udorn RTAFB. He logged 86 combat sorties over North Vietnam and Laos flying daytime and Night Owl interdiction missions against targets along the Ho Chi Minh Trail and against petroleum storage tanks in North Vietnam. Probably Sid's most notable mission occurred one day after the New Year's Day truce in 1967 when Sid was a wingman in the fourth of seven flights that comprised the famous Operation Bolo. Led by Robin Olds, the 8th TFW bagged seven MIG-21s in that one day (none by Sid). Clark Walker also flew F-4s in the 8th TFW as a member of the 555th TFS (the famous Triple Nickel) at Udorn. He reports that "Our squadron lost a full complement of airplanes and half of the crews during my tour." Clark would later return to the theater to fly with the 7th ACCS C-130 airborne command post.

Another classmate who was on his second rotation was Sam Waters. Sam was a FAC qualified F-105 driver with the 12th TFS in Kadena, and had deployed to Da Nang in 1965 where he flew some 53 combat sorties. He returned to the theater (Korat RTAFB) in November 1966 and resumed flying missions over North Vietnam. Sam was shot down over the North on December 13, 1966, ejected, and made it safely to the ground. He was declared MIA-NVN, although many believed he was being held in the Hanoi Hilton. The Vietnamese government returned Sam's remains to the US in 1976.

Cartoon by George Elsea

By 1966, all the restrictions about carrying Vietnamese observers and trainees in the O-1 had been lifted and O-1s were to be found throughout the theater, including Laos and North Vietnam. Gary Sheets was flying O-1Es with the Covey Special Operation Detachment, a "special one-time good deal" for Covey FACs in I Corps who would get time off their tour in exchange for 80 missions trolling for NVA targets north of the Marine positions along the DMZ: "The problem was that Marine forces were heavily engaged with the 324th North Vietnamese Army Division just south of the DMZ and there were no existing means of effectively thwarting the NVA re-supply. The topography in and north of the DMZ was varied from an agrarian, populated area near the eastern coastline to increasingly denser jungle cover and mountainous terrain moving westward toward Laos. It was in the western area where the NVA re-supply was concealed from cameras and fast moving aircraft." The mission of the Covey Special Operations Force was to find re-supply activities and then direct their attack by AF, Navy, & Marine fighter aircraft: "All 13 Covey FACs flew a two-hour mission every day, flying as a two-ship and at or below 2500 feet above the terrain. With the element of surprise we 'killed' dozens of trucks before they off-loaded their cargo for final transit south by bicycles on jungle trails, and on one mission a stray bomb ignited what turned out to be a huge ammunition storage area that we kept burning and exploding for three full days. Even from our tents in Dong Ha we could see the continuous black smoke, some 15 miles north. There was great rejoicing at all levels of the U.S. Command structure."

Over in Thailand, CT Douglass was not such a happy camper. He was in NE Thailand in early 1966 to finish out his one-year SEA tour establishing tactical air support parties and training Thai FACs. Unfortunately, there were no O-1 aircraft available in Thailand (they were all needed for more pressing duties) and CT did not speak Thai. Instead, he used a U-10 that the RTAF had made available. It had side-by-side seating (instead of tandem, like the O-1), which restricted his ability to work targets and instruct. One day, while CT was logging time in the U-10, he dropped into Nakon Phanom AB for some 'merican food and ran into Jack Brush. Jack was flying 0-2s east and northeast of NKP, but wouldn't say much about his operation . . . CT doesn't recall asking him, as they had too much other, personal, things to talk about (They had gone through BCT, 6th and 12th squadrons together). Unfortunately for CT, his Thailand assignment was a miserable experience: "lonely, austere conditions--living on the economy, without a weapon, in poverty-stricken areas, working for a Thai Colonel who did not want an American advisor on his base."

Obviously, not everyone from our class who served in the war did so as a pilot or navigator. Frank Mayberry was a communications officer who, in 1967, was responsible for the maintenance activities at seven Tactical Air Control sites in South Vietnam, after having cycled through Vietnam and Thailand TDY as a comms officer in the Philippines since 1965: "I was often at a site such as Ban Me Thuot when it came under attack by Viet Cong ground forces. I once came under direct AK-47 fire on Phu Quoc Island, but escaped unharmed. I was cited by both the US Air Force and The Republic of Vietnam Air Force for coolness under fire during the Tet offensive at Tan Son Nhut."

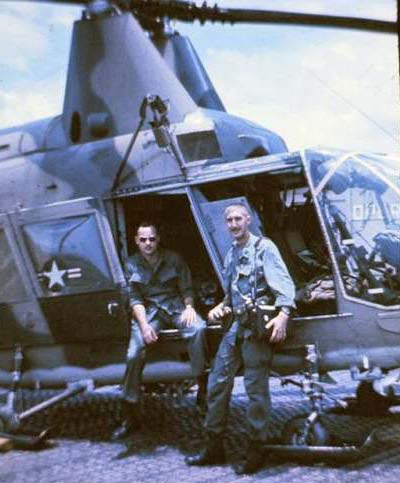

Dave Wiest on the right

In 1967, Don Stevens won his Air Force Cross flying his O-2A as a FAC on a rescue mission near Quang Ngai City in August 1967. A wounded US soldier was down and exposed on a beach and surrounded by two battalions of enemy soldiers backed by heavy automatic and 50-caliber anti-aircraft weapons. The following is an excerpt from Don's citation: "Captain Stevens made diving passes directly into the heavy enemy fire, and firing marking rockets between the advancing enemy and the soldier, directed USAF fighters to attack . . . the weather was deteriorating rapidly. Despite high volume anti-aircraft fire and a hit in the right wing, Captain Stevens, with total disregard for his own personal safety, persevered in his rescue attempt and succeeded in the safe extraction of the soldier and the reaction team that had gone in to help him." After two and one-half hours of constant exposure to withering enemy fire, Don landed at Quang Ngai airfield under minimum conditions on an unlighted field with no control facilities.

Ron Padgett

Ed Leonard

After years of unspeakable depredation and humiliation, and following the signing of the cease-fire in January 1973, Ed was repatriated on 12 February in the first contingent of 143 American PoWs. During the following weeks, the remaining 444 were released. The remaining LULUs, which Hanoi claimed were being held by the Laotian Communists, were among the last to be released. [Space does not allow us to do justice to Ed's inspiring story. Please refer to the class web site or the [50-yr Reunion] CD to learn more about his exploits and those of our other classmates mentioned in this section of the yearbook.]

In December 1967, Jerry de la Cruz arrived in Bien Hoa AB to fly the F-100. Greeting him there was Leon Goodson who was assigned to a sister squadron. Bien Hoa had been home to many of our classmates since the beginning of our involvement in 1963. One of that number was Mike Hyde, who was killed performing a napalm pass on 8 December 1966. During his tour, Jerry logged some 200 sorties and took several hits. Typical of the work horse F-100s, Jerry's squadron stood alert and flew the usual assortment of strike, close air support and Ranch Hand (spray defoliation) escort missions.

In May of 1968, Ed Haerter was back in theater with the 37th TFW at Phu Cat AB, SVN, this time as an F-100C pilot. During his tour, Ed was seldom bored, logging some 195 missions and 404 combat hours. On one of his missions, for which he was awarded the Silver Star, Ed virtually destroyed a NVA regiment that had trapped an Army SF 'A' Team in a valley surrounded by rugged karst mountains: "It was just a really scary mission, with 300' overcast, rain and growing darkness coupled with all sorts of anti-air: 23mm zip guns, 12 mm, and small arms fire. All this at 450kt indicated air speed."

Bob Fischer was one of the spray pilots at Bien Hoa that the F-100s supported. Jerry de la Cruz was also present during the Tet offensive in late January 1968, when sappers penetrated the base: "The ground fire was intense and all around us. As evening fell, flares were constantly being fired off overhead. I didn't care for the situation at all. I came over to Vietnam to fly. I didn't expect to be engaging the enemy in hand-to-hand combat or even at close quarters. Nonetheless, I had my weapon and I was prepared to fire on anyone that came close to our defensive position. Happily, the action wasn't near us."

The Tet offensive was a watershed event in the Vietnam War. Doug Rekenthaler was assigned to the Airlift Control Center at 7th Air Force Headquarters on Tan Son Nhut Air Base and living downtown when the Viet Cong struck. He was working his way back through town to the base after being recalled: "One old lady, squatting on the sidewalk, eating betel nuts in her black pajamas, smirked and said as we crawled past: 'Tonight you die, GI, tonight you die.' I thought she might be right. We lost numerous aircraft as VC sappers threw satchel charges into our aircraft, neatly parked in revetments and in orderly rows: shades of Hickam Field during Pearl Harbor days. In a final bit of irony, the base commander was, of course, promoted." Bill Zersen, flying a C-130 out of CCK (Taiwan), also survived a Tet sapper attack while TDY to Tuy Hoa. After spending the night hunkered down in a bunker, Bill emerged to find that, although several aircraft had been damaged, the Korean defense force had driven off the attack and killed seven VC in the process: "The ROK's, when we arrived at the flight line, had all seven of the sappers laid out on the tarmac. When I looked at them, I was shaken quite a bit. One of the sappers was the barber who had given me a haircut the day before and who had held a straight razor to my neck during the haircut. Never again did I have a haircut in Viet Nam." Although the Tet Offensive was tactical failure which decimated the Viet Cong cadres, its images on TV screens throughout America was in sharp contrast to the optimistic statements issuing forth year after year from MACV HQ in Saigon. The effect was demoralizing and cost President Johnson any hope of making a successful bid for reelection. By the end of the year, the Johnson administration had, in effect, placed a cap on US participation and began the process of putting the war back in the hands of the South Vietnamese.

Years of Withdrawal (1969-1975)

Ralph Lalime also joined the Triple Nickel, which Ralph claims, "had already shot down more MIGs than any other squadron in SEA." Ralph logged 180 missions (27 over NVN, 150 over Laos and three into SVN). His tour (1968-69) spanned the transition from the "win" strategy of the previous five years to the "get out with honor" strategy that was to characterize the post-Tet era. During his tour, Don Thurman, Greg Boyington, and several other Academy types were also assigned to the "Nickel" at one time or another. Charlie Folkart had flown with the 555th in 1967 when it was at Ubon and then transferred to the 13th TFS at Udorn in early 1968, completing his tour at Udorn as an Airborne Command and Control Officer in the 7th AF C-130 ABCCC. Gordo Flygare was also flying C-130s out of Udorn during this transition

Because Don Thurman was a test pilot school graduate, he also served as the squadron maintenance pilot and checked Ralph out in that function as well. Don also pioneered the concept of using the F-4D as a "fast FAC" and teamed with Ralph to log some impressive BDA numbers. On a day when both were scheduled to fly, Don and Ralph would scope out some potentially lucrative targets before the formal round of briefings began: As Ralph recalls, "Once airborne, I would check in with Don on a different frequency and he would tell me which of our cleverly designated targets were still there. Then he would go over to the ABCCC and tell them he had some good targets. I would separately go to ABCCC and tell them my flight's ordnance and availability. Of course we had dutifully briefed the targets given to us by HQ, but they were usually what we called 'tree parks' and ABCCC would always release us to Don. Upon leaving the tanker we would rendezvous with Don and he would either clear us on to the target or lead us to it. Having studied the exact picture on the map that morning, we all could clearly identify and destroy the targets. Over a period of a couple of months we were getting really good bomb damage assessments. I even had one guy from the other fighter squadron come up to me one day to ask how I was getting such good BDA!" In November, President Johnson halted all bombing of North Vietnam while allowing reconnaissance missions to continue--also allowing "protective reaction" strikes, if the recce birds were fired upon.

Two of Greg Boyington's claims to fame while with the squadron were: a) winning a samlar race by putting the Thai peddle-pusher in the passenger seat and doing the front end work himself, and, b) accurately dispensing CBUs on a target below minimums while flying straight up to get above the 7,000 ft. release altitude before pickling off his radar-fused cluster bombs.

While Greg was racing samlars in Udorn, either by coincidence or collusion, Al Johnson was accomplishing the same feat between the poles of a rickshaw during a mini-R&R in Hong Kong. Al was the navigator on an AC-47 gunship (Spooky) flying out of Da Nang. Late one night in a US Navy hangout in Kowloon, Al met two USNA lieutenants, and, at about 3:00 A.M, they decided to settle all issues concerning the relative merits of USAFA and USNA grads once and for all with a rickshaw race: "You can imagine the absurdity of the scene. Three Yanks pulling three Chinamen down a narrow street at breakneck speed--all six of us laughing and shouting the entire time. It was nip-and-tuck, but I dug deep. I called upon my fast-twitch muscles to carry me to a decisive gold medal victory! Another win for USAFA."

In 1969, Ken Biehle was flying refueling missions in KC-135s out of U Tapao AB, Thailand, as part of an operation called "Young Tiger:" "The majority of the refuelings were of flights of F-4s and F-105s, but we also did various other fighter and reconnaissance aircraft . . . We had a sign in the boom operator's window saying we were from Wright-Pat. One day a single F-4 was refueling and the pilot said, 'Wright-Pat, eh? Do you know Ken Biehle?' The 'boomer' said, "Yeah, we know him and he's right up here in the left seat." That was Don Thurman and he was flying Falcon FAC missions, presumably 'over the north.' We refueled Don on three other occasions and on the last one he told me he was pleased and excited that he had just received his orders to go to Edwards as an instructor after SEA. Sadly, he later died in a B-57 crash while instructing at Edwards. As a footnote, sometimes, after the disconnect from refueling a 'single ship,' the pilot would fly forward and position his aircraft 100 yards or so in front of, and slightly to one side of, our tanker and do an aileron roll before departing. The roll was not always executed real well and the pilot might even give it a second try. When Don Thurman did his . . . and he did it every time . . . he would do two rolls in succession, with about a half second hesitation in between and they were always absolutely perfect! The guy could really fly!"

Mike Loh flew 204 combat missions in F-4 Phantoms from Da Nang Air Base in northern South Vietnam in 1968-1969. Before his first mission over North Vietnam, his squadron operations officer called the new pilots and said, 'OK. We intend to write up each of you for a DFC during your tour. So, when you fly a really tough, heroic mission, have the members of the flight write each other up for a DFC, and the earlier in your tour the better. "So it came to pass that in late October, 1968, just before the bombing halt, Mike flew a particularly demanding mission attacking the North Vietnamese port of Dong Hoi and was duly submitted for his DFC. Later in his tour Mike became the squadron "Bullpup" guided missile expert and led many highly dangerous missions against NVA caves in Laos. One mission was spectacularly successful and Mike and his wingman submitted appropriate paperwork supporting a DFC recommendation. Here is Mike's report of what happened next: "When we approached our ops officer to submit the write-ups, he accepted my wingman's after checking that no one had yet submitted him for a DFC. Then, he turned to me and said: 'What the hell is this, Loh? Another DFC?' He checked his roster and said tersely, 'You already have one. Get the hell out of here!'" Mike goes on to say: "Now, whenever I see a DFC ribbon on the chest of an officer or enlisted person, I chuckle a bit, and recall all those Bullpup missions and my personal lesson learned about misguided combat medal policies."

In 1969, Quang Tri, a Marine base 20 miles south of the 17th Parallel, was the temporary home of both Howie Whitfield and Cres Shields. Living conditions were poor and morale was low. On this, his second tour, now flying the CH-46, Howie found that "The war had changed considerably, from a large U.S. buildup with optimistic expectations of winning quickly, to a long drawn out stalemate. It was frustrating for us, but excruciating for the grunts that had to go out in the field and continually go back over terrain they had assaulted six months earlier. There was no longer any sense that we were on a campaign to win. We flew a variety of combat support missions back in the mountainous jungle west of the field supporting the 3rd Marine Division. On one flight, during a troop assault on a small landing site carved out of the jungle, my CH-46D lost power in the approach and I had to crash land it on the hillside. Between our squadron and another CH-46 squadron at Quang Tri, we were losing an aircraft about every two-three weeks, due primarily to enemy action or pilot error. Overall, I ended up with 16 months in combat, flew 633 hours and 437 combat sorties." Howie also remembers running into Marty Richert, who was on standby at Quang Tri with his Jolly Green crew in anticipation of rescue missions to the North

Cres Shields was flying the OV-10 as a Covey FAC, and one day Ken Alnwick showed up on his doorstep looking for a ride. Ken was on sabbatical from DFH at the Academy doing a study on "Command and Control in I Corps." The next day, while searching for good targets up on Route 9, they encountered a US 9th Division tank that had lost a tread while being overrun by NVN forces and Cres got the call to destroy it. Several different flights from out of nowhere converged to take a shot at it, but tanks are really difficult bombing targets. After several failed Navy attempts, it took the Gunfighter F-4Es out of Da Nang to finally do the job.

George Luck

While George was dropping 500 lb iron bombs in Laos from a reconditioned WWII bomber, Charlie Diver was dropping 10-15000 lb bombs from C-130s over Vietnam in an effort to create "instant LZs." He describes a typical mission as follows: "When dropping the M121, the C-130 flew at an altitude of 5-6000 feet above ground level, and was guided to a drop point by Combat Skyspot ground radar. As navigator, I would determine the offset and call it into the ground radar, which would apply it to the Point of Impact, and the pilot would fly the headings given by the radar at the predetermined airspeed/altitude. At the drop point the loadmaster would release the bomb, hopefully it would sail out the back of the aircraft and not get hung up, and the rest would be history. Initially, the bombs were used for helicopter landing zones, but later, other targets were designated, and many of these targets would have a secondary explosion associated with our bomb(s)."

By 1971, President Nixon's "Vietnamization" program was in full swing while the Vietnamese Army and Air Force struggled to fill the void. Total US strength in Vietnam had shrunk to 184,000 from 555,000 in 1968--although the war along the Ho Chi Minh trail in Laos and Cambodia continued unabated.

Joe Higgins recorded it all while flying 140 combat missions in the RF-4C with the 14th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron from Udorn Royal Thai Air Base from June of 1970 to June of 1971. According to Joe: "By that time, folks had figured out that flying low would not be conducive to longevity, especially at night; so, the rules of engagement in 1970-71 called for not flying below 4500 feet and generally daytime only. Yet, 40% of the crews that were in the 14th when I arrived in 1970 were either MIA or KIA when I left in 1971. Most of my time was spent flying over Laos doing visual reconnaissance early in the morning, looking for guns, trucks, bulldozers, and storage sites."

In November, 1971, Mike McCall followed Joe to Ubon, flying as a fire control officer in the 16th SOS on an AC-130A gunship. He recalls that "Our primary mission was to 'kill' trucks on the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Laos, Cambodia, and SVN. We also provided close air support for troops in contact and downed airmen. In all, I flew 129 missions, and logged 590 hours combat flying time." Herb Eckweiler was at Ubon at the same time. Mike's greatest satisfaction came from Troops-in-Contact missions: "You get a call from an outpost on the ground, someone speaking only in a whisper. We would circle his position, pour in a few rounds of 20mm, and pretty soon he was speaking in a normal voice. No official recognition for these missions--just good feelings."

From 1972 to the end of the war, only a few of our class found themselves still participating in the SEA war games. One of these "lucky few" was Bill Goodyear, who, having flown B-52s earlier in the war, was flying T-39s for an organization known as Seventh Air Force Flight Operations, code name Scatback. Scatback aircraft typically flew established routes stopping at the Seventh Air Force bases in South Vietnam and 7th/13th AF bases in Thailand where they delivered processed film, official mail, and priority parts and picked up bomb-damage-assessment and gun-camera film. Sometimes, all of the seats were installed, and the aircraft would ferry high-level military and civilian VIPs. Bill's most unusual mission was to fly US Ambassador Elsworth Bunker's wife, Carol Laise, from Saigon to Katmandu (where she resided as Ambassador to Nepal) to attend King Mahendra's funeral. The 1700-nm trip took about four hours flying time and two refuelings to arrive at Katmandu's 6000-ft strip in a high mountain valley 4,390' above sea level.

In 1969, Pete King made a multi-generation transition from C-47 driver to F-4 pilot. He deployed to Cam Ron Bay later that year to fly the F-4 version of George Elsea's tree-busting missions. Two years later, Pete returned to the theater, this time to Ubon, to join the renewed air war over NVN, flying some 40 missions, including some that had him laying chaff for B-52s--on one occasion being fragged to lay the chaff on a target 15 minutes after the bombers had already dropped their bombs on it.

In about the same time-frame, two other classmates were in Saigon. Sid Newcomb was on his third tour, TDY to HQ MACV, Saigon, then NKP, Thailand, as target-validation officer, including duty on C-130 ABCCC over Cambodia. Once, when Tan Son Nhut was hit by mortar fire, Sid hid under his flimsy bed in his VOQ, and then later "watched the ops center displays in awe as hundreds of B-52s, escort fighters, and support aircraft flew over North Vietnam every night for a couple of weeks bombing Hanoi and vicinity, ultimately leading to 'truce' and freeing of our PoWs in early 73." Phil Meinhardt was assigned to the Vietnamese Joint General Staff in Saigon to coordinate U.S. support for the Vietnamese. Phil was the duty officer and the only American on the Vietnamese Compound: "During my tour, I was all over Vietnam, usually with General Trien (J3). The most memorable trips were to Quang Nai, Mo Duc, Pho Duc, and Pleiku during the North Vietnamese Easter Offensive of 1972. When the truce in Vietnam arrived, my job was to be one of the 200 U.S personnel allowed to remain to support the South. Everyone seemed to want my job; I wanted to go home, so they sent me to Nakhon Phanom, Thailand with the remnants of the U.S. Vietnam Headquarters (MACV). In Thailand, we carried on the war in Laos until a truce there and supported Cambodia. When the capital of Cambodia, Phnom Penh, was about to be overrun, I personally wrote the evacuation plan, nicknamed Eagle Pull, in 12 consecutive hours on a yellow legal pad. When finally executed in 1975, Eagle Pull successfully withdrew about 1300 personnel from Phnom Penh with no evacuee hurt or left behind."

Possibly Andi Biancur's most important Vietnam mission took place thousands of miles away from Saigon, in the current operations directorate of Headquarters Military Airlift Command (MAC), where he served as Chief of Current Operations. On 4 April, 1975, a Military Airlift Command C-5 Galaxy, tail number #68-0218, departed Tan Son Nhut AB, loaded with over 300 crew, children and adult escorts. Shortly after take-off the aircraft experienced an "explosive, rapid decompression" about 40 miles from Saigon. The plane could not reach the airport, but instead crash-landed at about 270 knots, two miles away into a field of flooded rice paddies, killing 138 people, including 127 of the orphans. When the news hit MAC HQ briefing room, Lt Gen Chappie James, then the MAC vice commander, turned, surveyed the staff, and ordered: " Biancur, get those people the f--- out of Viet Nam." He then stood and left the briefing. Andi immediately formed a small four-man tiger team to execute Chappie's orders. " Within hours, we had procured several wide-bodied aircraft from several U.S. civil airlines and had them in the air en route to Saigon and Da Nang. We worked alternate 12-hour shifts for the next three and one half months. By 1 August we had safely extracted some one hundred forty thousand people (including approximately 2,600 orphan children)."

In 1975, Mike A Clarke was a plans officer in the relocated MAC V headquarters at NKP. After participating in the Cambodian evacuation, he was assigned the job of developing the plan for the evacuation of US forces from Vietnam, an effort strongly opposed by the US Ambassador in Saigon as being " defeatist." Less than two months later, Mike's planning paid off, as he coordinated with Washington the minute-to-minute details of the extraordinary evacuation of the last remaining Americans and their Vietnamese compatriots from the relentless NVN onslaught. Previously, in 1964-65, Mike had flown F-100s over both South and North Vietnam.

Ken Alnwick, who was flying T-39s with Scatback out of NKP at the same time, was one of those who helped execute Phil's original plan for the evacuation of Cambodia and then, a few months later supported the Saigon evacuation. In 1972 Ken had been assigned to US MACTHAI/JUSMAGTHAI in Bangkok. He was variously, an O-1/OV-10 FAC advisor, a Command and Control advisor and a MACTHAI HQ staff officer, and regularly flew MACTHAI C-47 airlift missions into SVN. Ken took an in-country PCS to NKP in 1975: " Many of my missions were flown with TI Anderson from the Class of '59. We flew in and out of Saigon and Phnom Penh in the closing days of the war, and watched helplessly from above as the defenses around the Cambodian capital crumbled. We were on the ground in Saigon a few days before Saigon fell and watched Bien Hoa explode in a billowing cloud of smoke and soon thereafter witnessed the aftermath of the tragic fall of Saigon--12 years after the Class of '60 had first flown combat sorties off the runways of that unloved, but unforgettable air strip."

As a United Airlines 747 pilot during the latter stages of the Vietnam War, Rich (J.R.) Carter transported deceased soldiers back from Vietnam and he considered it a great and sacred honor to do so. However, Rich wanted a taste of what is was like to experience combat, and so, on one lay-over in Vietnam, he convinced a fighter pilot buddy to take him on a mission. He said it was an "incredible and pretty hairy experience" and that he was fine flying the transports after that flight. He often remarked, "All I have to do is remember all the boys I flew home from Vietnam and I realize that any problems I might have are really very small in comparison."

Perhaps Ron Yates best summed up our experience in what was, at least to this point, America's longest war: "Many of us fought in Vietnam using the wrong equipment and the wrong tactics. Worse, we had the wrong kind of leadership, both militarily and politically. I know those experiences molded the rest of my military career and my attitudes about the use of US airpower. It was those experiences that enabled Vietnam veterans, like those in the Class of 1960, to help build a new fighting force that would, in time, become the most powerful the World has ever seen. In that regard, Vietnam was not lives, treasure, and time wasted."

The following seven members of the Class of '60 were killed in SEA and are listed on USAFA's Graduate War Memorial Wall: Val Bourque (C-123, SVN), Bob Davis (A-26, Laos), Mike Hyde (F-100, SVN), Jim Mills, Capt USMC, (A-4, SVN), Eddie Morton (F-4, SVN), Sam Waters (F-105, NVN), and Reed Waugh (C-123, SVN). While he did not graduate with us, another Classmate, Jim Riley, Capt USMC, was also killed in SEA (Helicopter, Khe Sanh, SVN).

Beyond the Vietnam War

In Berlin on June 12, 1987, President Reagan said "Mr. Gorbachev, open this gate. Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!" For many of the Class of '60, this marked the beginning of the end of the Cold War that had played a central role in our military careers since the day we signed in at Lowry AFB. George Luck started his flying career on the front lines of the Cold War, flying B-52Hs in the 449th Bomb Wing at Kincheloe AFB, MI. Reed Waugh was also there as a B-52 copilot. During his five years at Kincheloe, George served 69 weeks on ground alert and flew 41 airborne alert missions. Concurrently, around the globe, classmates were standing alert in F-102s, flying long surveillance missions in EC-121s, or tending long range missiles or a host of other tasks designed to deter Soviet aggression. Twenty-five years later, George was still fighting the good fight: "I worked in J-3 Operations for the JCS. My first job was the nuclear weapons allocation officer. I owned the weapons stockpile and was responsible for its safety and security. Each year I prepared the allocation plan for the nuclear CINCs. My second assignment in J-3 was as Chief of the Command and Control Division in the NMCS. Among other things, I developed and maintained the go-to war codes, checklists and computers."

In 1963, Ralph Lalime was also on the front lines of the Cold War, flying F-102s out of Misawa, Japan. A Russian Bear (reconnaissance bomber) had penetrated Japanese airspace and Ralph and his lead were scrambled to intercept, ID and photograph the Bear: "We were off the ground in less than five minutes and vectored North/Northwest. Climbed out and leveled off at about 40,000 ft. We flew along in a loose route formation for what seemed a long time, but never made contact with the Bear we were chasing. Clouds were well below us and the radio became very quiet. Finally, I could see below and in front of us the largest landmass I had seen in over a year. We were still over the ocean but I could see miles and miles of coastline and even a large city on the coast. Trying to visualize the map in my mind, I figured we were North of Hokkaido, Northwest of the Sakhalin Islands, and must be pretty close to Mother Russia. I called out 'Red one, Red two.' 'Roger' came the reply. 'Let's turn around and go home.' As we flew South, we came back into a frantic voice contact with GCI. 'Red flight, be advised you have three flights of aircraft scrambling against you. Looks like two Migs coming up from the North, two more Migs coming from your East, and two more Migs coming up from your West! Recommend you RTB ASAP!' My leader pushed up the throttles, started a gradual descent and let the airspeed stay right around Mach one. Of course being a Lieutenant fighter guy, my thought was that I had six Migs surrounded and if lead could handle his, I could become an ace with the other five! Fortunately, we continued safely on home, with altitude and speed on our side and no further incident."

At about the same time, Bill Hockenberry, United States Army, was reporting to an elite reconnaissance unit, 3rd Squadron, 12th Cavalry, stationed in Germany. The 12th Cav was the cavalry squadron for the 3rd Armored Division (Spearhead), a famed division from WW II steeped in the tradition of Patton, occupying the Fulda Gap and constituting one of five American army divisions in Western Europe at the height of the Cold War: "My experiences during those years as a combat arms officer were forged by long-range patrols on the border, endless alerts, combat-loaded maneuvers, the tragic deaths of young troopers, unrelenting winter cold, and constant testosterone encounters with Soviet forces which gave new meaning to the term Cold War.

Dale Thompson

During May 1978, Angolan insurgents emboldened with Cuban forces and Cuban advisers, crossed intoZaire, formerly the Congo, into the interior of Africa to the town of Kolwezi, Shaba Province. France and Belgium agreed to aid Zaire: France provided the French Foreign Legion, and Belgium provided the drop aircraft. The US was involved in helping to organize a Pan-African force led by Morocco to be commanded by a Colonel-General of the Moroccan Army. They were to be airlifted by C-5s from their respective countries through Kinshasa for refueling and into Lubumbashi near Kolwezi. Tom Seebode deployed forward to be the Airlift Command Element mission commander. His team had two tasks: the first was to assist the Pan-African forces by airlifting them to Lubumbashi, and the second was to extract the French Foreign Legion. Living alternatively in austere and semi-luxurious circumstances, Tom used his Alphonso Mielhe third section French language fluency to smooth out stressful situations and successfully completed the three-week mission under difficult pol-mil circumstances in the heart of Africa.

Bill Kornitzer first became involved with the Iran hostage rescue mission in the fall of 1979, while he wasserving as the Deputy Director of Operations for the 437TH Military Airlift Wing at Charleston AFB, SC. Charleston's C-141s would be tasked to provide airlift support for 53 hostages, 120 members of the Delta Force team, 100 Rangers and as many as 56 helicopter crew members that would have to be extracted out of Manzariyeh, Iran. Extensive training would be required. Bill describes the mission: "After we were qualified to perform at night, we participated in numerous dress rehearsals with the MC-130, AC-130, KC-135 and RH-53 crews and the Delta and Ranger Forces. These exercises included mock surprise night assaults on active duty bases in the US and then departing before daybreak. These exercises were 19 monitored by high-ranking officers from Washington to ensure we were capable of doing the tasked mission. After we had successfully completed numerous exercises, our Joint Task Force (JTF) Commander, Major General James B. Vaught, U.S. Army, declared us ready to go and briefed the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and after that, President Jimmy Carter. On the first day of deployment for the actual mission, I flew with my crews to serve as the MAC on-scene commander at Daharan, Saudi Arabia and to then move forward to the extraction area at Manzariyeh, Iran as the mission progressed. Shortly after bedding down in Daharan, we learned that there had been an accident between a RH-53 and a refueling C-130 at the Desert One site. There were eight deaths and numerous injuries. We were told to leave Daharan immediately and fly to Masirah to pick up and treat the injured. We did that and then brought the injured and the Delta Force back to Wadi Kena. The injured, including burn victims, were transferred to MAC Medevac aircraft and flown to Germany. This was a very disappointing outcome for all of us who had worked so long and hard to make it a success. It was devastating to lose eight crew members in an unfortunate accident and to have to leave them behind. One remarkable thing about this mission was the scope; i.e., the distances and the amount of forces that had to be involved. It was also a tribute to everyone that this vast operation was kept a secret."

________

These stories are but a brief sampler of the contribution the Class of '60 has made to the safety and well-being of our nation since we last marched on the parade fields of our beloved Air Force Academy. We have visited every continent and flown literally hundreds of different aircraft from WWII hand-me-downs to the world's most modern military and civilian flying machines. Many have also achieved a significant degree of success and influence in the private sector. And, most of all, and never to be forgotten, many put their all on the line during their service, and some paid the ultimate price.

Thanks for the memories.